The post Reimagining the travel experience through hotel design appeared first on Without Limits.

]]>

‘Revenge travel’ – the desire to travel more, further and for longer after being unable to during coronavirus – has continued into 2023, after starting in 2021. The phrase started as a tongue-in-cheek concept on social media, but such attitudes are being reflected in travel data.

Travel to the UK has almost recovered to pre-pandemic levels. Visit Britain’s latest inbound forecast for travel to the UK in 2023 is 37.5 million visits – 92 per cent of 2019’s visitor figures. Travellers are forecast to spend £30.9 billion in the UK this year, 90 per cent of the 2019 spend in real terms, after taking inflation into account. This means the hotels sector, which suffered greatly in the pandemic, is enjoying a return to normality.

However, what constitutes normal is changing. People may be travelling more and spending more on travel, many using money they saved up during the pandemic – but their expectations are now higher. Hotel guests crave experiences, not just a place to rest for the night. In another evolution, tourists and business travellers alike are more conscious than ever of their carbon footprint.

The relative weakness of the pound against the dollar has also led to a changing tourist demographic. There has been a rise in domestic tourism within the UK, and for international visitors, a perception that the UK offers good value for shopping and leisure compared to other international destinations.

What does the next generation of hotels look like?

New hotels distinguish themselves by delivering a unique, memorable, highly positive customer experience. The building fabric and design is crucial to providing this.

Developers want to create ‘destinations’ – places where people want to be, see, and experience, even if they are not staying in a room there. These experiential aspects of a new hotel could centre around a rooftop bar, a ground level coworking space, or an art gallery, a music venue or a florist attached to the hotel lobby. The goal is to make hotel a place to meet and gather, not just to sleep.

Hotel design and visuals should be anticipated to be photographed and shared on social media, particularly among younger customers. YouGov reports four in 10 (39 per cent) under-25s now use social media platforms as their primary source of information when making travel bookings. Original artwork, unusual building features and high levels of biophilia are all ways to add appeal to Gen Z.

In contrast to the trend for providing a wide range of amenities, some hotels have scaled back on amenities and focus instead on providing low-cost, compact rooms designed for short stays. The growth of serviced apartments and aparthotels has also challenged preconceptions and expectations of what a good hotel experience should look and feel like.

Food and beverage (F&B) provision

Room occupancy forms the bedrock of a hotel’s profitability, but a successful food and beverage provision is now also important. As retail spaces reduce, hospitality is stepping further into F&B space. Socialising trends are evolving too, with food and restaurants now being a huge reason to meet and to travel.

When planning F&B and amenities, the local area should be thoroughly investigated. There is a nascent trend for new hotel developments to form agreements and partnerships with large local entertainment providers, such as stadiums. The post-pandemic return of big-ticket sports and music events with thousands of attendees has led to demand for nearby hotels to meet the spikes in accommodation and F&B needs of local major venues.

Health and wellness

Wellness is a buzzword. The Global Wellness Institute reports ‘wellness tourism’ is set to grow more than any other wellness sector, increasing by 20.9 per cent by 2025. In the hotel sector, this is reflected in increased demand for amenities such as yoga studios and access to wellness experts, classes, workshops and health retreats.

For hotel guests, the pandemic means there is a desire for antimicrobial finishes and passive measures to reduce the amount of physical contact users have with the building. This includes the introduction of kick plates to remove need to open doors using hands/door handles, and a focus on automatic sensor lights for rooms and toilets.

For hotel employees, everything at the outset should be designed to enable quick room turnarounds. Not only does this reduce cleaning times, but it can also improve the next guest’s experience, as the hotel is thus able to offer an earlier check-in.

Fire safety

Branded residences within hotels or aparthotels are making designing for fire safety complex. Branded residences are classed as residential spaces, and thus must comply with the Building Safety Act. The full ramifications of the new 2023 regulations may take some time to unfold, but it is likely to have a significant impact on project costs. The rollout of the new regulations is being monitored closely by industry.

Sustainability

Green travel is a booming sub-sector within travel, and customers increasingly want to stay in and associate themselves with hotel destinations that align with their values and green aspirations.

As a result, there is a strong shift towards new hotel developments achieving excellent or outstanding BREEAM (Building Research Establishment Environmental Assessment Method) ratings and showcasing sustainable developments to guests.

In a key shift since 2020, developers are now concerned with how to provide electric vehicle (EV) car charging infrastructure for their guests. There is a strong mechanical, electrical and plumbing (MEP) element to car charging provision, as it demands a high electrical load. The addition of EV charging also necessitates additional fire protection measures, further increasing overall costs to developers.

Redefining the future of hotel design

In a challenging macroeconomic environment, smart, efficient, flexible design will be critical to hotel profitability and success. Meeting stringent, data-backed sustainability and net-zero standards is also key to future-proofing buildings and attracting loyal customers who are proud to be associated with the hotel. In a world dominated by social media, providing great photo opportunities for guests and creating memorable moments and experiences is also key.

We are working at a time where the definition of luxury, high quality, business, and budget hotels is being redefined. We are redrawing the lines around what a hotel should look like, feel like and provide to users, with technology, economic and health considerations deeply influencing this. For industry, the challenge is being aware of — and responsive — to these rapidly changing norms.

Cost model: Mid-range, four-star new-build hotel

We have built a cost model that considers the design and cost associated with a mid-range four‑star new-build hotel of 12,000m2 GIA and 200 keys in central London. The cost range for a new hotel of this nature is wide and could vary from £4,000/m2 to £8,500/m2 depending on project specifics such as size, stature, site specifics, location, design and specification, area efficiencies and the extent of guest room or front-of-house offering.

Click here to download the cost model.

This is an abridged version of an article that was first published in Building magazine. You can read the full article by clicking here.

The post Reimagining the travel experience through hotel design appeared first on Without Limits.

]]>The post Building low-carbon commercial offices appeared first on Without Limits.

]]>

Rising public knowledge and concern surrounding the climate crisis are placing pressure on developers to deliver decarbonised buildings. People are increasingly demanding that their workspaces align with their values: research this year by KPMG found that 20 per cent of UK office workers would turn down a job if a company’s environmental, social and governance (ESG) factors were deemed lacking. Almost half of workers want their employers to demonstrate climate and social commitments.

Progress is undoubtedly being made in commercial office space decarbonisation. However, a by-product of the numerous guidelines, targets, and standards created to help us reach net zero means that there is not one single accepted definition of what a net zero building is. There are varying, and at times conflicting, rules for the industry to adhere to.

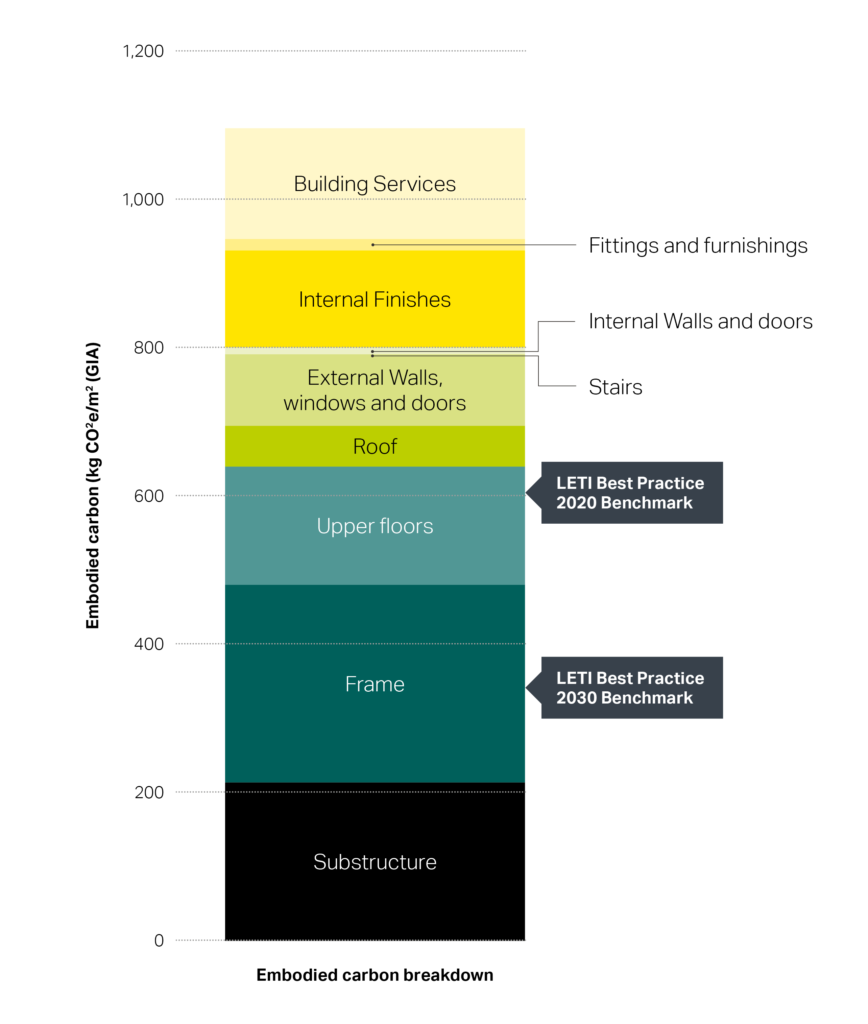

Complicating matters further, these metrics and guidelines are constantly developing and being refined. It is therefore important to set clear objectives of what we are looking to achieve. One useful – and ambitious – metric is LETI’s upfront embodied carbon emission targets. These apply for building elements at the product sourcing and construction stage, excluding sequestration. This targets 350kg CO2/m2 by 2030, with 50 per cent of building materials from re-used sources and 80 per cent of materials used to be able to be re-used at the end of the building’s life.

As of 2023, this target is not being reached – 500kg CO2/m2 is considered best in class. We use the 500kg CO2/m2 metric as our benchmark for a low carbon building targeting net zero in this cost model.

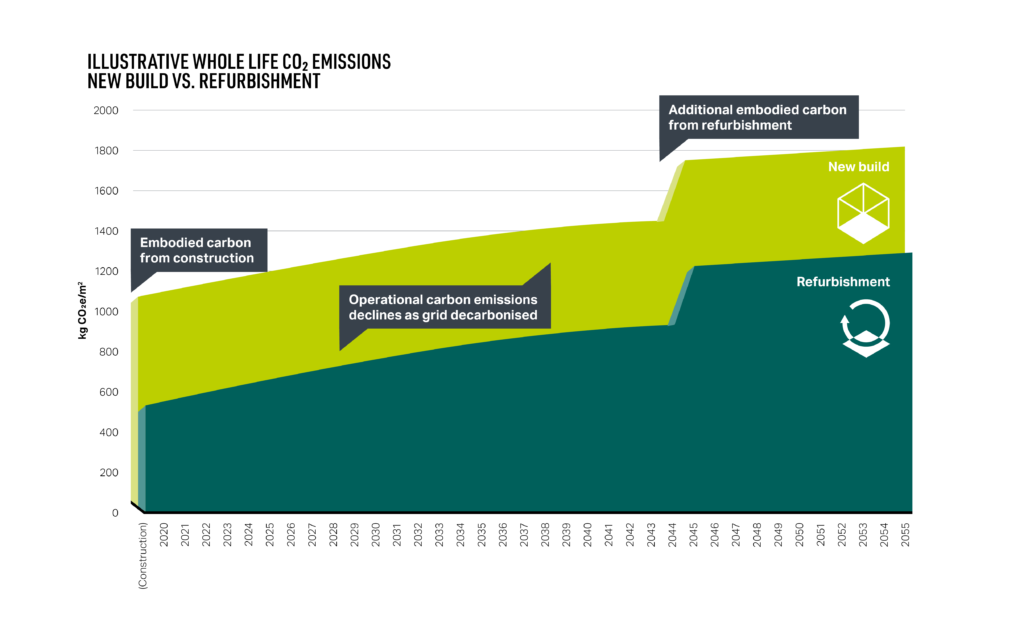

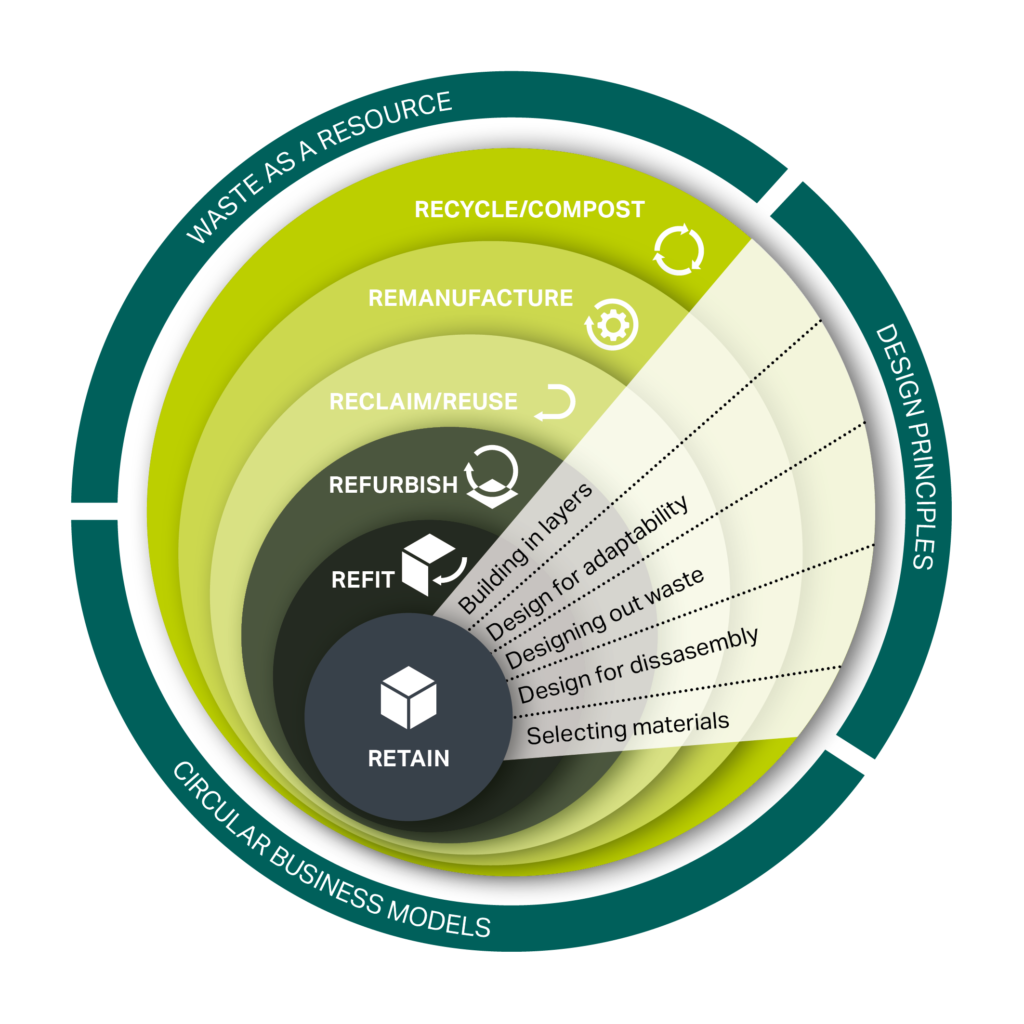

New build versus refurb

Embodied carbon is the most important and carbon-intensive factor to consider when designing for net zero. As the embodied carbon profile of a refurbishment project can be lower than a new build development, we are witnessing a shift towards a refurb-first approach to delivering projects across the UK. This is part of a general drive towards making the use of new materials in buildings a last resort, rather than first choice.

Yet choosing a refurbishment over a new build does not guarantee the lowest-carbon result. When measuring a project’s carbon profile, choosing between whole life versus upfront carbon measurements is a key factor to consider when trying to deliver the lowest carbon project possible. Typically, a refurbishment option will have a lower upfront carbon footprint. However, when assessing the whole life carbon of the building, the efficiencies associated with a new build scheme could close the gap.

Solid, accurate modelling and data are required to make sure the right assessments and choices are made as to whether to pursue a new build or refurb development.

Design considerations

The market (developers, tenants, agents) perceptions of what makes a Grade A office space need to include sustainability credentials, but this may conflict with other aspirations, such as the desire for large, open plan spaces. To meet these sometimes competing demands, traditional specifications should be challenged.

If retaining existing buildings, reviews of the product and the specification level required – or that tenants are prepared to accept – are essential for a clear design solution to be achieved. Lateral thinking is important. For example, some schemes are now prepared to embrace smaller column grids and less stringent environmental conditions.

When deciding what to re-use, and what to build or procure as new, the following design factors should be considered:

Sub-structure

- Basements. Our preliminary research suggests a basement could emit the equivalent of between two and three storeys of superstructure frame based on a typical single-storey basement of a mid-rise residential building. The industry is increasingly looking at how the basements inherited on schemes can be incorporated and re-used.

- Re-use of existing foundations/pile. The cost and viability of re-using and strengthening existing foundations should be the first potential solution to investigate, as it reduces the need to build new. With new sub-structures, the use of hollow piles, which reduce carbon by cutting material volume, can be considered. Precast, reusable, UK-sourced commercial hollow pile products are growing in use and availability.

Structure/Frame

- Concrete. Reducing concrete through design measures is the most effective way to cut the carbon impact of a project. Where concrete cannot be re-used or, in a new build, reduced through design, products are emerging to attempt to reduce its carbon intensity.

- Steelwork. The carbon intensity is influenced by the amount of steel specified for a frame, so the design should aim to minimise the amount of steel used. Reused steel can have a carbon intensity as low as 50kgCO2e/t, compared with a sector average of 1740kgCO2e/t for new steelwork.

- Structural grids and depths. A key driver for inefficient structural frame design is the current aesthetic preference for open spaces and concealed structures. By reducing grids, up to a point, significant efficiencies in the structure will be found in both the superstructure and substructure.

- Cross-Laminated Timber (CLT). CLT is a glued product, which can make it hard to break down, re-use or re-purpose. This may act at odds with circular economy principles and the sequestration benefits may be lost depending on the building’s end-of-life scenario.

MEP

- Recent calculations by the GLA suggest that services contribute 21 per cent to the whole life carbon output of a building. MEP decarbonisation is achieved by challenging norms; and optimising the efficiency of kit and its usage and control.

Finishes

- Developers are examining how they can dematerialise projects, cores, landlord and common areas that have the basic structure as the finish, sometimes with an enhanced finish from the original basic structure, without having to add further applied finishes to structure, which adds carbon.

Making net zero offices commercially viable

Net zero office buildings must evolve from being theoretical, to fully realised. For industry, the challenge is balancing cost versus decarbonisation. The overarching question is, how can we achieve lower carbon buildings in a financially viable way?

Right now there are more questions than answers. Existing norms must constantly be questioned if effective, consistent progress towards net zero is to be made. By making the most of disruptive technologies; choosing the most relevant, adaptable, low-carbon materials and processes; and by committing to industry-wide collaboration, we can answer these questions.

Cost model: Net zero offices

We have built a cost model calculating the cost and carbon of a new-build ground plus eight-storey commercial office building in a central London location. The report also includes a table which summarises the cost and carbon for two options to deliver the same overall size office building: the first is a complete redevelopment demolishing the existing structure and building new, and the second is a comprehensive refurbishment where the existing structure is retained and extended to achieve the same overall GIFA of 232,000 square feet.

Click here to download the cost model.

This is an abridged version of an article that was first published in Building magazine. You can read the full article by clicking here.

The post Building low-carbon commercial offices appeared first on Without Limits.

]]>The post How can urban planners influence the 15-minute city narrative? appeared first on Without Limits.

]]>The concept of 15-minute city has gripped public and political debate with opinions ranging from the simple and compelling views that locating most essential services and amenities within walking or cycling distance from our homes supports the shaping of sustainable communities, to the more extreme view that the concept infringes personal liberty.

Despite the strength of the concept, there isn’t yet a real-life example of a 15-minute city that has been built. Instead, the concept’s application in recent years has been mainly associated with the construction of cycling lanes, the planning longer-term low-traffic arrangements or sometimes with adding a bit more amenity in local neighbourhoods. So, with few meaningful reference points, the concept is highly malleable by media. If it is to be supported, it matters that the concept is used appropriately, maximising its full potential and not just focus on singular, mostly traffic-related applications.

As planners, to keep support for the concept, we need to ensure that our profession is aligned on the wider benefits of a 15-minute city and what it might look like, so that we can help reframe the narrative.

It’s about balancing the mobility network, not a battle against the car

Cities have an obligation to reduce transport emissions. It’s a complex task and reducing car use can only be achieved meaningfully when other low carbon, and as attractive, means of transport are provided.

People have the right to use a car, particularly in places where there are no relevant alternatives. The main question is when do we use the car, and what for? Better planning of local neighbourhoods will create choice, with more attractive, healthier, and safer options to move around. The car (hopefully a zero emission one, or a shared one) can then be used when needed but not as first choice.

The challenge is transition, as people are asked to change their behaviours and adapt to a new normal which impacts their daily routines. Whilst new developments such as King’s Cross, for example, prioritise walking and embed low traffic principles very successfully, residents and businesses that choose to locate there mostly buy into this from day one.

So, what can we learn from great places like King’s Cross? I believe its success is not just because of how well it has been planned but also because of the quality of place delivered (as well as how it is maintained and ran). Quality delivery is key to stimulating behavioural change.

Create and communicate the ripple effects of infrastructure

Cities must ensure that they can maximise the value of the investment in infrastructure, to create truly sustainable places. The 15-minute city concept can bring more benefits to local communities from infrastructure development, for example using the investment to spur regeneration around stations. Designing and delivering integrated developments around transport nodes helps maximise the value of the investment in infrastructure, delivering wider services than transport, such as housing and other mix of uses, within walking distance of the station – there are some great examples of this, particularly across Asia, such as West Kowloon Station in Hong Kong.

Looking beyond transport, larger developments present opportunities to rethink green and blue infrastructure including better and greener streets, a more attractive network of public open spaces and parks including spaces in buildings such as sky gardens and green facades, delivering comfort, microclimate protection, biodiversity, and other sustainability and place making benefits.

Stratford and the Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park in London is a great example where planners leveraged the value of the park and concentrating high-density development around transport nodes, shaped a range of places that are highly walkable, vibrant and safe for local communities, workers and visitors.

If embraced by local communities and when making economic sense, integrated sustainable infrastructure can become one of the most positive catalysts for shaping the future of our cities.

Settling the challenge of business district vs suburb

One of the challenges about the 15-minute city concept is the negative impact its local focus – and supporting more working from home – might have on central business districts (CBD) which thrive on an ecosystem of people coming in to work by public transport, going out for lunch, and socialising in the evening.

However, this isn’t the case of one against the other. Good cities are planned as a holistic network, where central urban areas and suburban neighbourhoods complement each other.

In Sydney, Australia, there is now a strong push to make the CBD relevant again, not by attracting 9-5 workers back, but by diversifying the offer as a mixed-use piece of city, attracting a much wider range of businesses as well as residents, around a 24/7 environment.

In Melbourne, the city’s largest infrastructure project in decades – the Suburban Rail Loop (SRL) – presents a once-in-a-generation opportunity to revive suburban environments by making new stations focal points for new ‘centres’. This supports the city’s long-term plan which promotes ‘living locally’, providing people more services and opportunities closer to home.

Delivering much needed change to the city’s building stock

With most of the decarbonisation efforts now focused on retrofitting existing stock, the 15-minute city offers an opportunity to do a ‘deep dive’ into local areas.

Following the coronavirus pandemic, many employees have seen their offices getting a much-needed facelift with more collaboration space and a friendlier, more relaxed environment – attracting workers to come back to the office, for at least part of the week. Local high streets and town centres, which have struggled to adapt to the change in the retail landscape following the rise in online shopping, have seen new uses like wellness, shared workplaces, galleries and local artisans take up vacant retail units.

These new uses encompassing retrofits are a fantastic opportunity for cities, enabling significant gains from a carbon perspective but also enhancing place quality and experience. For urban environments, which usually take years to adapt and evolve, there are opportunities to increase the pace of change.

Conclusion

The 15-minute city concept isn’t a ‘one size fits all’ plan. It is not meant to be a perfect model for new city living, simply because there isn’t one. It is there to present and guide to a different future – shaping more liveable places, healthier and more sustainable communities.

There is much more to the 15-minute city than how we move around. If considered holistically, it gives us useful tools to balance global challenges of climate change, economic instability or health and to balance those with the needs and aspirations of local communities. As urban planners, we should align behind these wider benefits so that the narrative moves on from the concept simply being about car use or working from home.

This article was originally published in The Planner.

The post How can urban planners influence the 15-minute city narrative? appeared first on Without Limits.

]]>The post Decarbonising real estate starts with intelligent planning and design appeared first on Without Limits.

]]>Reducing the carbon impact of existing building stock is a time-critical task for the industry, as the consequences of human-induced climate change are now tangible. In 2022 alone, the UK experienced its warmest year on record, according to Met Office data. The past year has also seen heavy rainfall, flooding, urban wildfires, and other extreme weather conditions in the UK and on a global scale – all of which are being experienced with increasing frequency.

The scale of the decarbonisation challenge cannot be underestimated. Existing building stock accounts for approximately 23% of UK carbon emissions, according to a 2019 Royal Institution of Chartered Surveyors report. In the housing sector alone, the UK Green Building Council estimates that the UK’s 29 million homes must be retrofitted at a rate of 1.8 every minute to achieve net zero by 2050.

The public sector

Despite immense funding pressure, the UK public sector has in many cases led the way in estate decarbonisation investment. Initiatives such as the Public Sector Decarbonisation Scheme (PSDS), launched by the Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy, are injecting cash into improving public buildings by stripping out carbon and energy inefficiencies.

The PSDS has to date provided around £1.6 billion in grant funding to help public sector organisations improve the energy use of existing buildings, and to reduce their reliance on fossil fuels. Additionally, the Public Sector Low Carbon Skills Fund provides grants for public sector bodies to engage specialist advice to develop decarbonisation plans for their estate.

The private sector

For private estate owners, the investment case for decarbonising their buildings centres around both highlighting their ESG credentials and preventing assets from becoming stranded. Assets become stranded when their value is vulnerable to external factors such as changing regulation, technological innovation or evolving social norms.

In real estate, legislation preventing assets with poor energy efficiency from being occupied is a growing risk. There is also rising pressure from fellow asset owners: initiatives such as the Net-Zero Asset Owner Alliance requires members to reduce emissions across global property portfolios.

To mitigate this risk, tools are emerging to help estate owners assess the likelihood of their assets becoming stranded. The European Union (EU)-funded Carbon Risk Real Estate Monitor (CRREM) is a tool that allows investors and property owners to assess the exposure of their assets to stranding risks based on energy and emission data and the analysis of regulatory requirements.

Factoring energy efficiency into design

Cutting carbon by increasing energy efficiency typically involves improving the thermal efficiency and air tightness of the building fabric, along with the installation of energy-efficient plant and smart building control technology. Energy assessments will provide guidance on what is possible at each site.

A fabric-first approach is important. Improving mechanical, electrical and plumbing engineering (MEP) systems in a building with a poorly performing external envelope has limited value. In contrast, upgrading facades, adding insulation, and increasing air tightness are all effective interventions and are often the first point of focus when taking on a retrofit challenge.

That said, improving the heat efficiency of the building fabric can often create an increase in whole-life carbon. Given their carbon intensity, is only advisable to undertake full cladding replacement if the existing system is damaged, performing poorly or nearing the end of its useful life. A holistic approach should be taken to considering the impact of building fabric changes – overheating and condensation, for example, can be consequences of failing to consider how a replacement building fabric will interact with existing building components.

Once decisions about the external fabric and structure have been made, it is important to understand how a building is used. Heating, cooling and lighting unoccupied space is costly in both monetary and carbon terms, yet if building occupier patterns are fully understood, this is a relatively easy way to quickly cut carbon output and energy costs.

This can be done through installing building-level controls to enable efficient building management. Controls are key to ensuring energy use is minimised and the benefits of natural ventilation are explored and incorporated where feasible. Incentivising efficient occupier behaviour is another important way to reduce energy demand.

Introducing onsite renewable energy generation capability is something developers are often keen to explore, as it is typically a highly visible example of a building’s efforts to be more sustainable and can help achieve higher EPC ratings. However, it should be noted that as electricity sourced from the national grid decarbonises, the operational carbon benefit of onsite production lessens.

Full grid decarbonisation is still decades away, but we are swiftly moving towards renewables becoming the dominant source of on-grid power. Onsite generation has other valuable benefits, such as energy security and the potential to sell energy to the grid, but electrification of existing plant has the biggest impact on carbon reduction.

Creating holistic decarbonisation plans

For real estate owners that are yet to consider these issues, thinking ahead of time and having a plan in place for estate decarbonisation will enable them to be nimble and take full advantage when new funding streams or supportive initiatives are announced. Tax policy is one area in clear need of greater government support. That UK policy currently favours new build developments over refurbishment is bewildering in the face of our climate goals, and needs to change.

Public sector support – directly through grant funding, targeted initiatives, and regulatory change – is key, but is only one part of the solution. Private sector action on estate decarbonisation is crucial and is an important part of the jigsaw which cannot be ignored. More instruments are needed to accelerate this market, whether in the form of a carbon tax, or a shift in the relative prices of gas and electricity or other solutions.

The construction industry, the financial community, and asset owners must all pick up the pace on estate decarbonisation if both the UK’s and other international carbon targets are to be achieved. In the face of soaring inflation, a recession, labour and materials shortages and a lack of knowledge in the sector on the topic, it is an indisputably difficult task. Success in these conditions may be about trade-offs and compromises – and collectively creating holistic decarbonisation plans to break the decarbonisation challenge down into achievable steps, one project or estate at a time.

Cost model: Estate decarbonisation

We have built a cost model for the core baseline costs for different interventions that should be taken into account before building a more detailed, and informed, view of project-specific costs. Indicative cost ranges provided in this cost summary are in Q4 2022 prices and rates reflect the national average.

You can download the cost model here.

This is an abridged version of an article that was first published in Building magazine. You can read the full article by clicking here.

The post Decarbonising real estate starts with intelligent planning and design appeared first on Without Limits.

]]>The post Designing logistics centres that can keep pace with demand appeared first on Without Limits.

]]>After a turbulent period which started with Brexit and was sustained by coronavirus, materials, labour and supply chain issues have now been ramped up by the conflict in Ukraine. Wider economic inflation, in turn, is driving costs to all-time highs.

Yet the most surprising thing about the logistics market at present is that it is buoyant in the face of these staggering materials price hikes. The industrial market has experienced double-digit increases on build cost over the past eighteen months – leading to an incredibly challenging time for market participants, where demand is high, but supply of key elements is low.

Logistics buildings typically have a very simple design, comprising an envelope of structural steel, a concrete slab, and then cladding on the walls and roof. However, with steel and concrete now in high demand and low supply, logistics centres’ need for large amounts of steel means costs and delays have become particularly pronounced. Steel and concrete are also energy intensive products to produce. As energy pieces rise, production costs have also soared.

How inflation impacts procurement

The typical procurement route for this building type is changing. A previous preference for single-stage tendering is now changing in favour of two-stage tendering, and to a more partner-based approach. Many of the bigger developers are even bypassing two-stage tendering – instead, going straight to a partnership with a contractor at an early stage, in order to try and lock in prices and contractor availability.

January 2022 saw some of the sharpest materials price increases on record. To offset building costs, rental prices are rising on units. This shift in yield has helped upcoming and in-development projects to continue to be financially viable. The problem developers face doing deals going forwards is how to predict build cost, and whether deals can be achieved on a fixed-price basis.

Design with end use in mind

The biggest change with this building type over the past decade has been the shift to ecommerce, which now dominates demand. All retailers are assessing their ‘dark lstores’ and last-mile facilities and want to use them to help gain a competitive advantage over rivals – by ensuring their logistics centres enable the fastest and smoothest order fulfilment.

While logistics centres are relatively simple in design, there are differences in facility layouts and heights based on what stage and type of fulfilment they are catering to. Last-mile logistics centres typically have a ground-based operation inside the building. They do not require high racking and are often laid out like a supermarket, with staff doing the picking rather than shoppers. In contrast, larger distribution centres, perhaps leased or owned by major international online retailers, feature high bay racking, and often deploy greater levels of technology and robotics for picking products.

Therefore when developing a shell, it is important to consider the expected end use. For example, a fulfilment centre which has heavy amounts of robotics may need to reconsider the use of roof lights, windows, and sources of natural light, which can confuse robot tracking and motion sensors.

Amenities for the people who working in logistics centres are improving, as labour shortages make it more important to attract and retain workers. Some core features are found in almost every project – such as a canteen, showers, changing and toilet facilities, and a large car park. However, gyms, sports fields, trim trails and additional EV charging points for staff cars and grassy outdoor meeting or relaxation areas have all been included in recent projects, to attract tenants and retain labour.

To maximise value, some tenants are opting to make their distribution centres also their HQ or primary office location. This may also drive-up demand for enhanced staff amenities and increased office design. Offices are typically fitted out to Cat A.

Making logistics centres sustainable

Because logistics centres are such large, open spaces, the cost impact to improving sustainability is relatively small compared to the cost of the building itself. BREEAM Very Good is easily achievable with speculative logistics developments, and is now a baseline; BREEAM Excellent status is also being reached on some projects where tenants have demanded it.

Logistics centres, with their large flat roofs, are obvious choices for solar PV installation and this is now commonplace. Some developers are selling the electricity generated from their rooftops to tenants. Making logistics centres self-sufficient from an energy perspective will likely become a strong selling point soon.

Location also informs what sustainability measures can be included. Rainwater harvesting, on-site wind turbines, EV charging points at every delivery van space and water attenuation are all being deployed on projects.

A smarter and more efficient future

Rather than a case of ‘survival of the fittest’, where only the largest contractors or tenants can take on and manage the risk associated with the inflation happening on these projects, it may turn out to be survival of the smartest – those industry players who can collaborate with the right partners; secure prices, labour and materials as efficiently as possible; and keep watch and respond to the retail trends which are influencing demand for these buildings.

Cost model: Distribution warehouses

We have built a cost model for a shell logistics building in a central UK location. The parameters are set around a gross internal area (GIA) of 159,900ft² (14,855m²), including a 475m² office fitted out to category A, powered by a pure electric system. Unit rates are derived from competitive design and build tenders and current at 3Q 2022.

You can download the cost model here.

This is an abridged version of an article that was first published in Building magazine. You can read the full article by clicking here.

The post Designing logistics centres that can keep pace with demand appeared first on Without Limits.

]]>The post How carbon and wellness principles are driving office design appeared first on Without Limits.

]]>Coronavirus is not fundamentally changing office design. Home working, hybrid models, hub-and-spoke offices, ‘resimercial’ design – all of these concepts were in existence long before early 2020. The pandemic has merely acted as a catalyst for their growth, propelling them from trends to established norms.

What has changed is employee expectations of what constitutes a ‘good’, healthy, productive workplace. The balance of power has shifted towards the employee, and their needs are now influencing office design just as much, if not more, than their employers. Working three days at home and two days in the office is no longer a benefit that must be ‘earnt’ or negotiated. Instead, it’s an expectation.

After two years spent working largely from home, employees are now more educated and engaged in hybrid alternatives to the fixed-desk office than ever before – and are willing to leave or join companies if they cannot offer working patterns and office spaces that fit their lifestyles, as seen in the ongoing ‘Great Resignation’. So how can office design attract and retain talent?

Standards are emerging to support decision-making

There is no one-size-fits-all solution, trend or model that will define what makes an effective, future-proofed office that promotes the wellbeing of its users. However, standards are emerging to help give developers a sense of what is important to consider at the design stage.

The WELL Building Institute’s WELLNESS scoring criteria offers 10 concepts to consider when building with wellness in mind from air quality and light to materials and mind. Achieving specific, defined targets within the above concepts means a building is awarded points which can be used to achieve the WELL standard. Accreditation is evidence based and must be verifiable and presented for outside input.

Furthermore, AECOM’s Strategy+ design consultancy studio equips clients with a proprietary wellness audit, which assesses the wellbeing of an organisation with metrics that go beyond tangible elements and physical assets before designing a fit-out. Some of the factors that influence office wellbeing are objective: achieving a building certification, for example. Others are subjective, such as the presence of support networks and access to mental and physical health resources.

Factors such as employee absenteeism and attrition, staff autonomy, the presence or absence of reward systems, strong CSR and ESG strategies, the promotion of positive behaviours towards colleagues and KPIs related to wellbeing are just a handful of the metrics we measure in order to gain a picture of the ‘wellbeing maturity’ of a business. From there, we can design offices which meet the specific well-being needs of the organisation.

Designing for the future

Rather than instigating new office models, coronavirus galvanised existing trends such as hybrid and agile working, pushing them into the mainstream. Instead, we think it is wellness, sustainability, and the legal challenge to achieve net zero by 2050, that will be the overarching drivers of innovation in office fit-out design, costs and materials moving forwards.

For the industry at large, delivering office fit-outs that consistently achieve these high standards of wellbeing on both new-build and refurbishment schemes will require a radical overhaul of the way we plan, commission, design and build projects. Here are just two examples:

1/ Is fit-out Category A still fit for purpose? In an era of low waste and sustainability, is the Category A model still fit for purpose? For some office builds, arguably it is. For open-plan office spaces with a simple design, a lot of the principles of Category A fit-outs still work well, with the majority of the materials and design used being able to be retained. But the more bespoke an office is, the less Category A is suitable. Offices of the future will need to accommodate hybrid and agile working practices, and these models require bespoke fit-out solutions.

A better option may be increased uptake of the ‘landlord contribution’ model, where the landlord gives a fixed amount of funding towards the tenant fit-out as part of the lease agreement, to create a fit-out that meets a tenant’s own specifications.

2/ Circularity: beginning with the end in mind. At present, there are few examples of fit-outs that truly embody the principles of low carbon sustainability, wellness and circularity. However, the WELL standard is making wellness easier to benchmark, offering a glimpse of what could become the norm.

As an example of an office project with wellness designed in, one Manchester office with a WELL Platinum rating incorporates air-quality monitoring and filtering to achieve a constant Excellent VOC rating, at least 50 per cent of the furniture is second hand — including reclaimed desk chairs that had been earmarked for landfill. The lobby’s welcome desk appears to be made of marble but was produced from recycled yoghurt pots. Such choices helped cut the fit-out’s embodied carbon to 120 kilograms of embodied carbon per metre squared, compared with the 180 to 220 kilograms estimated for a standard fit-out.

As employees decide how they want to work, and who they want to work for, employers have a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to re-assess and reset what their office spaces represent and stand for. We advocate a holistic, individualised approach to office design. This ethos encompasses not just the fixed physical assets of an office, but prioritises active carbon reduction principles, makes use of behavioural science and building data, and quite simply, delivers a workplace that people feel safe, motivated and excited to come back to.

Furthermore, smart businesses should take advantage of this unique moment in time and work to future-proof their company against perhaps the biggest risk facing us all right now – climate change.

Office fit-out cost model

We have developed a cost model based on a notional fit-out for a space for 1,000 full-time equivalent staff, using a sharing ratio of 50 per cent.

You can read the full article and download the cost model here.

This is an abridged version of an article that was first published in Building magazine.

The post How carbon and wellness principles are driving office design appeared first on Without Limits.

]]>The post Assessing the cost implications of the upcoming Building Regulations revisions appeared first on Without Limits.

]]>Introduced by the Department for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities (DLUHC), the new regulations are primarily driven by the pursuit of the UK’s legally binding net-zero 2050 goal. The updated rules have also been influenced by the coronavirus, which has made clear the need for effective ventilation in buildings, particularly in high-density shared spaces such as offices.

These updates are setting the stage for larger changes in three years’ time. These uplifts are an interim – and preparatory – measure ahead of the much wider-reaching Future Homes Standard and Future Buildings Standard, which are due in 2025 and will apply to new homes and new non-domestic buildings respectively.

What will change?

The specific elements of the Building Regulations to be affected by the upcoming changes are Part L and Part F. Broadly speaking, Part L addresses carbon emissions and energy efficiency, while Part F is concerned with delivering good indoor air quality by delivering sufficient ventilation and minimising the ingress of external pollutants.

The headline element is the requirement for a 27 per cent average cut in operational carbon for new non‐domestic buildings (with a 31 per cent average cut for new domestic buildings). Thanks to increasing recognition of the need to reduce carbon emissions, some parts of the industry are already well prepared for the changes. The London Plan, for example, means that similar requirements to many of the changes introduced by the 2022 regulations are already in force. In the capital, it may well feel like business as usual for developers.

The design and cost implications

A flexible approach is essential to ensure the most effective solutions are found based on individual project constraints. Under the regulations, a theoretical ‘notional building’ is used to set a feasible target across different building types. The CO2 emissions and primary energy of any proposed building should be equal to or better than that of this notional building, which has the same size and shape as the proposed building, but is built to a standard ‘recipe’ of U-values and building service efficiencies.

The developer has the option to vary the specifications and relax some parameters relative to the notional building, as long as other parameters are improved beyond the notional specification, so that ultimately the CO2 emissions and primary energy are as good as or better than the notional building. This is intended to allow for flexibility – a mix-and-match approach, enabling certain design choices to be offset by other elements of the building.

Technological advancements and increases in supply chain capacity for more energy-efficient products have eased pressure on the cost of meeting the new regulations. For example, solar panels, LED lighting, and triple-glazed windows are all energy efficiency measures that are significantly cheaper today than they were in 2013, when the regulations were last updated.

The attractiveness of electricity as a power and heat source has also evolved. The carbon intensity of electricity dropped significantly over the past decade, in large part due to the rapid increase of renewable electricity feeding into the UK energy system. Building regulations previously favoured the use of gas as an alternative to electricity – a situation which the new rules reverse.

Looking to the future

The most important takeaway is that the new regulations are part of a wider shift towards highly efficient buildings where low levels of carbon – both from an emissions and an embodied carbon perspective – are the rule, rather than the exception. In adapting to the new regulations, our key advice is:

- Timing is important. The rules do not change overnight – this year, developers need to assess whether they will fall under the old regulations or must comply with the new.

- If developing a project that falls under the new Part L, then it is vital that the impact of this is considered at the earliest opportunity.

- The regulations are likely to drive a national shift away from fossil-fuelled heating towards heat pumps and other low carbon sources.

With the far more ambitious Future Homes and Future Buildings Standards set to go into technical consultation next year ahead of their introduction in 2025, the industry should aim as high as possible when designing out carbon, and is advised to drive up efficiencies and invest in innovation in order to remain compliant. As ever, it is best to be ahead of the curve rather than behind it.

Full cost model

We have built a cost model assessing the impact of the changes to Part L for three types of non-residential building: an out-of-town commercial office; a central London commercial office; and a large distribution centre. Analysis compared differences between notional buildings meeting the 2013 and 2022 regulations. You can read the full article and download the cost model here.

This is an abridged version of an article that was first published in Building magazine.

The post Assessing the cost implications of the upcoming Building Regulations revisions appeared first on Without Limits.

]]>The post Reducing operational carbon on commercial and educational campuses appeared first on Without Limits.

]]>Organisations, educational institutions, and companies with large campuses must decarbonise their real estate. In many cases, this is a complex challenge as each individual building – whether recently-built or 100 years’ old – must be made more energy efficient to reduce the amount of operational carbon used.

Historically, this might have been done on a project-by-project basis. To meet publicly stated climate emergency declarations and net zero carbon commitments however, organisations, institutions and companies will need to take a different approach, or risk reputational damage.

In this article, we argue the case for the adoption of a comprehensive decarbonisation plan on commercial and institutional campuses as the best way to reduce operational carbon in the most time and cost-efficient way. Furthermore, a comprehensive plan can also reduce reliance on increasingly expensive and bureaucratic carbon offsetting schemes.

1/ A piecemeal approach won’t cut it

Currently, there is a common knowledge gap between setting net zero targets and understanding what role decarbonisation plays on that journey, and how it can be achieved. Decarbonisation is not as simple as replacing gas boilers with heat pumps (as doing so greatly increases running costs). Instead, we strongly advocate that any action to reduce operational carbon by moving away from fossil fuels should be considered in the context of all ongoing maintenance and must touch all capital works.

2/ If you can’t measure it, you can’t manage it

Establishing a baseline for how well an estate is performing is the first step, along with general condition of the plant and fabric. If not already available (as part of either planned maintenance or maintenance backlog information), then an extensive survey will be required. Our Operational Carbon & Energy ANalysis tool (or OCEAN for short) gathers data on carbon and energy performance of individual buildings so that holders of large asset portfolios can understand how their entire portfolio is performing.

If not already installed, adequate metering is a good investment as it is essential to understand how an estate is performing to determine where or when to make interventions. Furthermore, once a solution has been implemented, it is equally important to then monitor performance.

3/ Make better use of space

Once a baseline has been established, the buildings and systems should be evaluated to determine whether space could be better used and/or operational hours consolidated.

In universities for example, where the pandemic has accelerated the trend to online study at home complemented by collaborative in-person sessions, the way space is used on campus has altered dramatically. Managed correctly, this is an opportunity to reduce energy demand by delivering learning in selected spaces that are shared between departments and faculties, and thus used more intensively. Similarly, the creation of night hubs allows parts of an estate to remain open out-of-hours while the majority closes.

4/ Develop a decarbonisation plan

The next step is to develop a decarbonisation plan for each building that considers fabric, lighting, controls, and plugged-in load. The plan should consider the opportunities for reducing operating temperatures to allow heat pumps to be used, and the possibility of using thermal storage. A decarbonisation plan needs to be built into the planned maintenance and plant replacement schedule along with an adequate budget commitment over the identified decarbonisation period.

Finally, each project needs to be delivered in sequence to ensure an institution can decarbonise in line with its publicly stated goal. Having switched to a lower energy approach with all electric services, organisations should subscribe to a certified zero carbon electricity tariff to complete the process.

Essential and achievable

Adopting a comprehensive plan to reduce operational carbon on a commercial or educational campus is essential – and achievable. In our experience decarbonising commercial and public real estate across the region, the most effective campus-level plans are informed by an organisational-level net zero transition plan. It’s the best way for firms and educational institutions to identify opportunities that save carbon, time, and money in the short and longer term, while providing assurance to stakeholders, customers and students.

The post Reducing operational carbon on commercial and educational campuses appeared first on Without Limits.

]]>The post Cutting the carbon in structural frames appeared first on Without Limits.

]]>In the race to meet net zero by 2050, there is positive news for those working in the built environment – operational carbon emissions in the sector have dropped significantly in recent years. This is because better technology is creating energy efficiencies, but it’s also happening because both government and industry have taken operational carbon emissions seriously.

In contrast, embodied carbon is much harder to quantify, and has suffered from a lack of consistent benchmarking, research and data. This lack of reliable information has made it tough for government to set informed, regulation-backed, reduction targets. However, as embodied carbon’s share of total carbon output expands, and operational carbon continues to shrink, this will soon change, making it important for developers to be ahead of the curve.

Digital tools will be key to quantifying embodied carbon

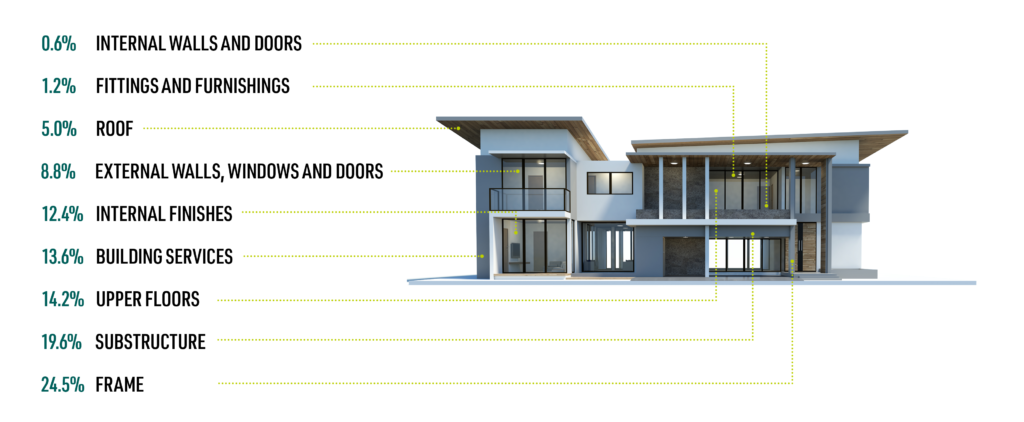

The structural frame of a building is one of the biggest sources of embodied carbon in a building: reducing this carbon therefore needs to be centre stage and influence every decision made in the design and construction process.

For industry, the ability to swiftly and accurately assess the embodied carbon impact of a wide range of structural options will be essential to achieve genuinely low-carbon or net zero buildings. However, there are often wide variances in knowledge, experience and awareness of embodied carbon across different clients and design teams. That’s why the creation and implementation of digital design tools from the earliest conceptual stages of a building are going to become increasingly valuable and critical.

Doing this effectively requires access to real-time data to immediately demonstrate the carbon and cost implications of design options – we have developed the Eco.Zero digital design tool to enable this process.

digital design tool to enable this process.

Cutting embodied carbon: a complex, multifaceted task

Whilst the embodied carbon of the frame and substructure is significant in itself, it also interfaces with a multitude of other systems – façade, partitions, finishes and services, for instance. These systems all interact, so to offer a true reduction in environmental impact we always advise a holistic approach to early stage life-cycle carbon assessments.

For example, column-less floorplates are currently desirable, but need much deeper spans of steel to counter vibration frequency – adding carbon and cost to the design solution. Materials also present a balancing act. Brexit has impacted on the cost of importing lower-embodied carbon materials, such as European electric arc-furnace produced steel. The obvious answer is to use local, home-grown materials instead – yet this can also have negative impacts on the carbon profile of a project. The UK may have its own home-grown steel supply, but 80 per cent of it is produced in coal-fired blast furnaces, which emit higher levels of carbon.

Therefore, when assessing the embodied carbon footprint of a structural design, a whole-life approach which identifies all potential carbon emissions, at all phases of the eventual building’s life – from the pre-construction phase to decommissioning – should be used. It’s a tall order, and one that is best done at the earliest stages of the project, when the ability to influence the design and maximise whole life cycle carbon reductions is at its greatest and the cost in doing so is at its lowest.

Where we’re headed

Despite the challenges, the industry can no longer ignore the issue of embodied carbon, nor can we work in silos when it comes to reducing it. We all need to be on board – carbon needs to be considered right from the outset as a core part of the building’s design, purpose and value.

There is no one-size-fits-all option, no perfect material or design that is inherently the best option from an embodied carbon and cost perspective. Instead, decisions have to be made on a project-by-project basis, incorporating as many variables and considerations as possible and making the most of the technology and data that is available to us at present.

The availability, quality and interoperability of embodied carbon data will make a huge difference to the pace at which we progress in reducing embodied carbon. We’re in the infancy of having widespread access to reliable, comprehensive carbon data across all elements of a building, which will allow developers to make smart, informed choices.

As embodied carbon in buildings becomes more and more understood and recognised, right now, the most effective solution to reduce it is to deploy the best of emerging data and materials technology – whilst also staying mindful of time-honoured techniques of being frugal and thoughtful with materials use, designing with simplicity and functionality at the fore.

Comparative cost and carbon model

We have built a comparative cost and carbon model have been made of the following frame types: reinforced concrete flat slab; composite rolled steel with metal decking, steel frame with cross laminated timber slabs and a cross laminated timber, glulam and steel column hybrid. Models are based on a new build commercial office building in a central London location with a gross internal area of 10,500m2.

This is an abridged version of an article that was first published in Building magazine. Click here to read the full article and download the cost model.

Additional contributions from Jack Brunton, David Wong, Colin Campbell and Kelly Forrest.

The post Cutting the carbon in structural frames appeared first on Without Limits.

]]>The post The delivery of affordable housing in Ireland needs to be accelerated appeared first on Without Limits.

]]>Coming out of the pandemic, Ireland’s housing crisis, north and south, cannot be ignored. Yes, the possibility that more people will work, more often, from home opens exciting possibilities for different types of living away from urban centres, but our key workers must still be able to get to their jobs from affordable homes near suitable transportation.

And both the Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland have a critical lack of affordable housing. By March 2019, there were 37,859 applicants on the social housing waiting list in Northern Ireland, of whom 26,387 were in “housing stress”. Resolving this is a key focus for the Northern Ireland government, with Belfast 2035 growth plans targeted at delivering 32,000 new homes. It is also a priority for the Irish government, with Project Ireland 2040 including plans to increase overall housing supply by 25,000 homes a year by the end of 2020, and then 30,000-35,000 annually up to 2027.

It will not be easy for public bodies to overcome their struggles in delivering housing. But these housing goals are a start, and by working closely with experienced project managers and using the full range of resources and consultants available, there is a way to achieve them. Moreover, a new approach to public transport and compact urban development could allow for housing to be better targeted in a joined-up approach that is badly needed. Project Ireland 2040 is demonstrating the right approach to rail and housing by aiming to secure over 50 per cent of future housing needs in existing built-up areas.

Procurement and planning must be streamlined

From the outset, the procurement process in the Republic of Ireland is complex and time-consuming. In the UK, established design team frameworks enable a streamlined procurement system for developing a brief, a business case or a feasibility study in a matter of weeks. In the Republic, that process can take months.

The planning process itself can also be slow, expensive and risky. Whilst changes in planning legislation to allow major housing developments go directly to the planning appeals board has brought more definition to some elements, the changes have also led to a steep rise in demands for judicial review. Given that a judicial review can take two years to proceed, this can seriously frustrate the planning process.

A Housing Task Force could resolve these issues, with a focus on project management, including both public and private sector team members. In the Republic of Ireland, there are many different agencies involved in the development of a single affordable residential scheme (starting with local authorities, An Bord Pleanála, Irish Water, Environmental Protection Agency and the Department of Housing, Local Government and Heritage), with each agency working to its own timescales, priorities and budgets. An empowered overarching Housing Task Force could focus on delivery and move blockers.

In planning, it is vital to keep the process moving, resolving bottlenecks and ensuring that an application doesn’t get stuck on someone’s desk. At AECOM, we have seen plenty of instances where good project management has helped with large-scale planning applications and streamlined processes. In Burgess Hill in southern England, for example, we are the lead consultant on the Northern Arc project, a major development being promoted by Homes England, that will deliver up to 3,500 new homes. Using our Masterplanning IE technology-based approach we achieved local authority approval for the masterplan and infrastructure delivery plan in under four months. Outline planning permission with a signed legal agreement was achieved in 16 months.

This accelerated programme was made possible by stakeholder co-operation and the creation of a masterplan that was supported by the gathering of all the necessary technical evidence. For example, flood risk and drainage technical expertise was deployed from the very start of the project. This allowed sustainable drainage systems to be integrated into the masterplan, mitigating the impact of climate change on fluvial flooding. A problem that might have reared its head after months or even years of planning work was resolved from the outset.

“In planning, it is vital to keep the process moving, resolving bottlenecks and ensuring that an application doesn’t get stuck on someone’s desk.”

Managing viability issues

In both Northern Ireland and the Republic, there are issues around the financial viability of projects. Even with planning permission achieved, the projected cost of development can wipe out a positive return from potential sale or rental revenues. Less than 30 per cent of projects granted planning permission through the Strategic Housing Development planning route have commenced on site.

Assessing viability has also been made more complex by the pandemic. Developers are having to work out whether more working from home is a long-term trend or whether people will return to the office within months. Making long-term decisions that will affect people for decades is a challenge when there are so many moving parts. An effective Housing Task Force would help address these viability issues.

Either way, it is likely that some workers will embrace home offices, and there is also a growing awareness that daily long-distance commutes are not environmentally desirable. Essentially, developers have to find a way of creating financially viable new homes close to urban centres for keyworkers while also finding a way to accommodate people who are able to live further away from their workplace.

One way of accelerating the development of affordable housing is to further explore the options for state-owned land that could be suited to quick development. This is advancing quickly with the establishment of the Land Development Agency in the Republic. The state land portfolio includes many sites with viability challenges. The challenges range from utility infrastructure deficits to significant protected structures including historic health and defence buildings. At face value, the development of these sites may seem challenging, but when broader economic benefits as well as the carbon benefits of retrofit versus new build and the long-term cost of the ‘do nothing’ option are considered, the argument for development is compelling. The AECOM Economics team has developed models for taking a broader view on such developments.

Resolving obstacles to implementation

After planning and viability comes actual implementation, and there are major challenges facing the Irish construction marketplace today. The industry lacks the resilience and scale needed to invest in modern methods of construction that are cheaper and faster, and reduce the carbon footprint of developments.

Government support could aid such innovation, as without it, the implementation of major schemes is very difficult. For the construction industry to grow as required, the government needs to establish a pipeline of upcoming work for those prepared to invest in their methods and materials. The key priority must be to develop effective masterplans that accelerate and improve every element of property development, enabling smooth implementation of affordable housing developments.

“The key priority must be to develop effective masterplans that accelerate and improve every element of property development, enabling smooth implementation of affordable housing developments.”

Affordable housing is too serious a problem to be allowed to drift on. The challenges faced by public bodies charged with delivering affordable housing are significant and public bodies often lack the expertise and experience to deliver the quantity of housing necessary in a relatively short period. But there are projects such as Burgess Hill that demonstrate a way forward, showing that the harnessing of the vast range of skills and resources available in the private sector can lead to effective collaboration and progress.

The post The delivery of affordable housing in Ireland needs to be accelerated appeared first on Without Limits.

]]>The post Improving data centre delivery through an integrated approach appeared first on Without Limits.

]]>Described by some industry commentators as the ‘new oil’, data is expected to increase 10-fold worldwide between 2017 and 2025, with 75 per cent of the global population interacting with data every day, according to International Data Corp. Driven by the growing use of mobile technologies and cloud computing by both businesses and consumers, this relatively ‘new’ global data industry is growing — and fast.

New investment opportunities

To cope, more data storage space is needed. This has led to a boom in data centre construction, bringing about significant opportunities for further investment in this alternative but growing asset class — globally, data centre construction is set to expand by more than 8.24 per cent to US$32.37 billion (€29.04/£25.5 billion) between 2018-2025. For example, in the Middle East alone, rapid digitisation of ‘smart cities’ is spurring the data centre market, which is expected to grow annually by 7 per cent between 2018-2024.

Growing demand

To keep up with demand for ‘white’ or data storage space, the data centre industry is under pressure to bring resilient, efficient and secure infrastructure and facilities to market quickly. In response, hyperscalers and operators are increasingly looking to complete site selection, acquisition, design and construction work as efficiently and innovatively as possible.

Integrated data centre delivery

We believe it is possible for the industry to increase speed to market through integrated, multi-disciplinary delivery across a data centre’s journey to completion.

Inception – Selecting a suitable site with appropriate power and utilities is fundamental in getting projects off the ground. Our integrated approach starts from project inception with site selection, masterplanning, environmental screening and planning permissions. Our planning experts share their in-depth knowledge and experience of navigating the complex data centre planning process with our designers to ensure designs meet essential requirements needed to obtain permission.

Design – We develop design briefs collaboratively with clients and appropriate stakeholders. Working as a single, multi-disciplinary team enhances collaboration, driving faster delivery through seamless and efficient handover between disciplines. This ensures a flexible, resilient design that fits with the client’s requirements to ultimately satisfy their end customers more efficiently.

Delivery – Working closely with the client, our integrated team of architects, engineers, environment and planning specialists share knowledge of the various customer, planning and construction requirements to achieve a better, more adaptable solution. Our construction related services including on-site environmental monitoring, project management and cost consultancy ensure projects are kept on the right track, through to client handover.

Data centre delivery in the Middle East

AECOM was engaged by a global corporation to design new build data centre campuses on three sites in the Middle East.

Our specialist UK and Ireland Centre of Excellence data centre teams collaborated with local in-country offices on the due diligence process for an initial critical load of approximately 4MW per data centre complete with a shell and core suitable for 15MW, as well as an overall masterplan of 90MW per site.

During the design stage, which was achieved in five months, a significant value engineering exercise was completed to offset the impact of increased cooling loads resulting from the high local temperatures.

As a result of effective engagement with local statutory authorities, all planning, building and utility permits were successfully obtained and AECOM was subsequently retained to provide construction supervision services to the client’s construction management team.

The depth of specialist data centre design knowledge held within our Centre of Excellence data centre team, coupled with the in-country teams’ local knowledge that helped coordinate the permitting process, was key to the successful delivery of this project, with all parties recognising the importance of seamless communication throughout the design and construction phases.

Furthermore, we supported the local construction team throughout the build, ensuring any on-the-ground design changes were controlled and complied with the overall base design.

The benefits of an integrated approach

Improves information transfer: Integrated working reduces the risk of information being lost between disciplines/organisations, due to fewer interfaces. This is particularly relevant during the data centre design permitting process when the feedback loop between environmental and planning specialists and designers is continuous, producing updated versions of reports or further iterations of design, requiring a high degree of collaboration.

Streamlines communication: Data centre clients receive a single point of contact, as opposed to several, streamlining all communication, from daily and weekly progress and coordination meetings to engagement with the local authorities.

Drives overall efficiencies: Procuring and managing just one entity drives overall savings and greater efficiencies through reduced administration. It also avoids duplication of efforts and resources as well as the untimely coordination of interfaces.

The post Improving data centre delivery through an integrated approach appeared first on Without Limits.

]]>The post Going underground: untapped land uses beneath our feet appeared first on Without Limits.

]]>While Hong Kong has a long history of using underground space for commercial and public facilities, many of these projects were simply an extension of the building on top of them, with limited connection to the city around them. As urbanization continues its upward trend and our perceptions of space — personal and public — are constantly evolving, this use of layered technologies to explore the underground holds the potential to revolutionize urban liveability and create synergies with the surrounding urban context.

AECOM, commissioned by the Civil Engineering and Development Department (CEDD) of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region (HKSAR) Government to undertake a study of underground development in an urban space, has explored ways of integrating the latest innovative technologies, including Virtual Reality (VR) and photogrammetry technologies with more widely used techniques in the industry, such as Building Information Modeling (BIM) and 3D spatial data to improve communication among the different parties involved in the planning and design process of underground space.

This novel combination of technologies has resulted in time savings, increased efficiency and cost benefits as well as greatly enhanced cooperation and the ability to virtually collaborate without the need for travel to a project site. On one project, outlined below, the use of photogrammetry technology to create a 3D model of the existing site saved three weeks time from the site survey, while sharing the site reality model with the designer for performing the parametric design saved another two weeks. Integrating various feature models into a visualization model for the Virtual Reality simulation saved another two weeks by amalgamating information to form a holistic review with different parties. Further, it saved client comment time as 3D visualizations facilitate the design detail and constraints of the project. Since the design team did not need to travel to Hong Kong, this saved around $100K HKD.

Particularly in high density cities, where land value is high and greenfield developments are hard to come by, the ability to map the underground more effectively and efficiently may open a world of possibilities.

This combination of technologies was first used to see how an urban park in Honk Kong that is close to a railway station could be better integrated to its surrounding area. The park is surrounded by densely developed multi-story buildings of mixed residential, commercial and retail use. For initial planning, AECOM and CEDD wanted to capture the existing environment in a 3D model to study how the park related to a wide range of facilities at ground level. But while there was 3D data on the buildings surrounding the park, there wasn’t any available 3D data on the park itself. That’s when we started going underground.

To build a more complete picture, we used Hong Kong government 3D spatial data[1] from the Lands Department to create that 3D model of the park then combined it with aerial photogrammetry technology. We shared the resulting model – complete with hard and soft landscaping and areas of interest within the park – with our partnering architecture design company based in Japan who had enough detail to be able to do many things that would usually have required travel to Hong Kong. This included measuring the space, seeing the topographic setting and the detail of the proposed site, as well as gaining an understanding of how the underground project would relate to the existing environment.

In the early stages of the design, a BIM model was created using the architectural design model which allowed all parties involved to communicate effectively and with a great level of detail. The BIM model was then combined with the site reality model (3D + photogrammetry) to create a Virtual Reality (VR) model that could be experienced on a computer screen. This virtual environment gave designers, planners, engineers, consultants and client representatives a realistic and life-sized place to walk and talk through the various aspects of the project.

After we layered on the virtual reality component, the resulting 1:1 representation of the project site also enabled 360-degree panoramas suitable for mobile VR devices used at in-person public consultations, as several mobile devices can be deployed at one venue. Panoramas can also be hosted on a website to reach a wider audience. The next level we’re exploring is a computer-connected VR device which would allow for more detailed design review and for users to interact with the virtual underground space design at a real-world scale. These representations could also be used in a virtual consultation room using AECOM’s interactive web-based tool.

Another benefit to this layering of technologies is that visualization models are not limited to the illustration of design details; data can be converted to other software to view shadow, noise and traffic impact assessments; 4D (BIM) simulation can also help to visualize the construction process.

This approach is unique because the novel integration of these innovative technologies has rarely been investigated within the framework of a single project and never-before used to explore underground space. Stakeholders often think only of BIM, but with an open mind this concept can be (and has been) replicated with different combinations of the various available technologies to suit the needs of other clients and projects.

Our study demonstrates the clear benefits for all parties involved in the planning and design of the conceptual scheme for underground space development in densely populated urban areas. Designers, planners, clients and consultants can visualize the components of a design at a 1:1 scale in ways that cannot be matched by 2D or 3D software alone. For the public, the realistic nature of the VR-based model brings the project and its full potential to life.

Learn more about this and other explorations of the potential of subterranean space to revolutionize the future urban experience in the new book Underground Cities: New Frontiers in Urban Living, introduced here.