The post Transport and mobility: Brisbane 2032 to reimagine Australia’s fastest-growing capital city appeared first on Without Limits.

]]>The South-East Queensland region is experiencing a population boom, and Brisbane is the fastest-growing city in Australia[1]. The Games are the stimulus to bring forward planned infrastructure, delivering targeted improvements to regional public transport while accelerating the energy transition. This investment in mass transit connections, zero-emission buses, walking, cycling and micro-mobility facilities will be the Games legacy for a better-connected South East Queensland region for generations.

The International Olympic Committee notes that carbon emissions from the movement of people and goods represent a key environmental impact[2]. Brisbane 2032 will be the first carbon-positive Games, meaning it will remove more emissions than it produces. This aligns with Queensland’s Zero Emission Vehicle Strategy and Queensland Transport Strategy, which aim to realise air quality, health, sustainability, accessibility, resiliency, and productivity goals.

Understanding the transit landscape

To deliver a carbon-positive Games, an innovative and effective Transport and Mobility Strategy is needed to ensure every investment choice, planning decision and design outcome considers carbon impact and ongoing community value far beyond 2032.

“In Brisbane, targeted investment in improvements to active transport facilities will support zero-carbon mobility at a local level,” says Carla Schnitzerling, AECOM’s Technical Director – Transport Planning, Queensland. “This includes access to Games venues with improvements to first and last-mile connections between a transport node and venue to further encourage an uptake of public transport.”

Host cities have long relied on strategic rail connections as a centrepiece of mobility, offering efficient mass transit. Brisbane 2032 will be held across Brisbane, the Sunshine Coast and the Gold Coast, and the rail network will be critical to intra-regional connections. Significant work is underway to progress the planning and delivery of rail network enhancements and Brisbane City Council has made ambitious first steps to envisioning what a transport and mobility strategy could look like for Brisbane 2032, with the extension of the safe and accessible Brisbane Metro network.

Buses will also continue to play a significant role for key cities in the South East Queensland region. The ambition is to deliver a significant zero-emission bus fleet and associated depot and charging infrastructure, and the development and delivery strategy for zero-emission buses needs particular focus to be Games-ready. This is a necessary and critical step to enable athlete and spectator mobility while reducing the Games’ carbon footprint. It will create a legacy of assets, increasing mobility for communities and reducing environmental impact. However, the pathway to transition to an electrified fleet and infrastructure is complex, and competing demands for resources across jurisdictions with other states’ similar priorities, add to the complexity.

The challenge of improving the transit network is heightened by the critical need to simultaneously address climate change through decarbonisation. This is achievable but relies on accelerated decision-making, delivery, and prioritising investment to create a legacy Queenslanders can be proud of, well beyond any sporting success.

With such ambitious targets and a notable infrastructure program to deliver over the next eight years, what will underpin Brisbane’s success?

The Games Venue and Legacy Delivery Authority will steer the Brisbane 2032 Transport and Mobility Strategy to deliver accessible and sustainable travel choices, accelerating travel options that will serve the region’s communities before, during and following the Games. The development of this strategy needs to be accelerated to move planning into delivery with a focus on:

- Delivering travel options for all – ensuring viable alternatives to private car travel

- Increasing travel by public transport and active transport

- Improving access to opportunity (Jobs, Education, Healthcare, Sport + Leisure)

The current public transport system can only serve 50% of projected trips to Games venues[3], so prioritisation of investment is needed to deliver the target of 90% of journeys by public transport and active transport to venues[4], which will include:

- Mass transit – Rail (Cross River Rail, Direct Sunshine Coast, Logan to Gold Coast Faster Rail) and BRT/Bus (Brisbane Metro, Zero Emission Buses) and Electric Ferries;

- Walking, cycling and micromobility – Improvements to dedicated facilities for walking, cycling and micromobility, including for first and last mile connections; and

- Innovation and technology – Advanced Air Mobility, Demand Responsive Transport / On-Demand Transport; Intelligent Transport Systems; Mobility as a Service; Smart Ticketing; Integrated Information and Wayfinding.

South East Queensland is on the cusp of a transformative era in transportation and mobility. The Brisbane 2032 Transport and Mobility Strategy is the first piece of the puzzle, priming the state to set a new standard of universal, inclusive and accessible design. Government, industry and the public will all be key to move strategy into action, working together to deliver multiple complex multidisciplinary projects simultaneously.

Learn more about how AECOM is shaping Brisbane 2032 into a lasting legacy here.

Footnotes:

[1] Source: Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2023, Data by region, accessed 13 August 2024, abs.gov.au/databyregion

[2] According to https://stillmed.olympic.org/media/Document%20Library/OlympicOrg/IOC/What-We-Do/celebrate-olympic-games/Sustainability/sustainability-essentials/IOC-Sustain-Essentials_v7.pdf

[3] Department of the Premier and Cabinet, 2032 Olympic and Paralympic Games Value Proposition Assessment, 2019, pp. 9

[4] https://q2032.au/big-picture/sustainability

The post Transport and mobility: Brisbane 2032 to reimagine Australia’s fastest-growing capital city appeared first on Without Limits.

]]>The post The catalyst for change: how we helped London win the bid for the 2012 Summer Olympic and Paralympic Games appeared first on Without Limits.

]]>With its looming pylons, breakers yards, derelict buildings and an epic fridge mountain, the site that would become the Olympic Park was a largely run down and melancholic place a decade before the 2012 Olympic Games opening ceremony. However, with the growth of the capital shifting eastwards, revived interest in urban living, and with Mayor Livingstone’s pledge to improve quality of life in east London, it provided the opportunity for one of Europe’s largest regeneration projects, a home for the 2012 Olympics and a new future district for London.

Let’s start at the very beginning. How did AECOM’s involvement with London 2012 begin?

Bill Hanway (BH): “Our involvement began way back in 2003. We worked with Barbara Cassini, first chair of the bid committee, and Mayor of London Ken Livingstone who saw an opportunity to deliver improvements that would help balance the east of the capital with the more affluent west. The London 2012 bid was conceived in the spirit of Barcelona 1992, with regeneration as its focus.”

The early masterplans were key to providing confidence to the International Olympic Committee (IOC) that London could – and would – deliver transformational change. Tell us more about those early stages.

“To prove to the IOC that we could deliver, we needed to make the bid ‘real’ so gaining planning permission for our first masterplans from all four host boroughs was crucial. However, granting simultaneous permissions from multiple boroughs had not been done before.

So – across the course of a very long day – representatives from Hackney, Waltham Forest, Tower Hamlets and Newham each had a different room at City Hall, and they worked simultaneously to deliver the permission. This was quite a feat at the time and a real achievement. I believe it really helped seal the win.

It’s also important to note that we created parallel masterplans for the legacy and games right from the start. It meant we were designing for the future of London, with the catalyst of the Olympics as an event along the way.”

Tell us about the day you found out that London had won the bid.

BH: “A group from the AECOM office joined the crowds in Trafalgar Square to hear the announcement (it was July 5, 2005). Paris was the favourite alongside Moscow, Madrid and New York City. You can imagine the excitement when International Olympic Committee President Jacques Rogge announced from Singapore that London had beaten the other four other cities to host the 30th Olympiad. I’ll never forget that moment.

As the excitement wore off, the enormity of the task ahead began to sink in. We knew the challenge was immense, not just the physical work on the park, but also making sure all the socio-economic change was delivered. We knew that it would take amazing feats of collaboration to bring it all together.”

With the bid won for London, what came next?

“Work began right away on setting up the right delivery bodies, including the Olympic Delivery Authority led by David Higgins, and preparing compulsory purchase orders to bring the fragmented landholdings required for the Games into public ownership. All of this was critical to making London’s Olympics happen on time and on budget, and to provide the theatre for the games followed by the creation of a new park for London, thousands of new homes and jobs, sporting facilities and amazing transport connections.”

The AECOM-led consortium of designers was rank outsider to win the competition to design the London Games, yet we won. Tell us more.

BH: “Although we had created early masterplans to win the bid, the Mayor held a competition to design the full-scale event. The battle was between us and high-profile names including Terry Farrell, Hertzog & De Meuron, Foster & Partners and Richard Rogers Partnership (as they were known then).

We were the rank outsiders. The Evening Standard had the odds for us at 100-1 (we had joked about placing a bet!). So – despite our belief that we had the best approach to delivering the games and an integral strategy for the legacy – winning came as a huge surprise.

I think we won because we wanted the London Games to be very different to Beijing (which we were also working on at that time). We didn’t go for big iconic architecture. Instead, our masterplan focussed on regenerating the whole area with then new 560 acre park at its core, cleaning up the river through the heart of the site, building in sustainable solutions wherever we could, and maximising what could be achieved in the legacy after the games. Our aim was to make sure that 80 pence in every pound spent on the park had a legacy use.”

How did the global economic collapse in 2008 affect the Games?

“Without question, hosting an Olympic and Paralympic Games is expensive, disruptive, and carries risks. The Games are delivered on a seven-year cycle that does not always match global economic patterns. However, London 2012 hit the cycle at the ‘right’ time and the low construction costs driven by 2008 financial crisis helped keep costs under control.

We were also able to bring in the best talent, so the projects were extraordinarily well managed and delivered.

At the time it was felt that the slow economy meant it would take a generation to complete the legacy building, but in fact much of that work has now been achieved over the past ten years, and in some ways exceeded the original expectations.”

How did you feel as the opening ceremony drew near?

BH: “There was an intensive focus on completion of the park and main venues in the months before the opening ceremony. As a result, a number of facilities were completed ahead of schedule shattering the historic perception that London could not deliver an epic construction project on time. I feel very proud of that achievement.”

“At 7.30 on Friday 27th July it felt like the whole nation fell silent for the opening ceremony. There were millions of smiling faces, and, for us, a huge sense of relief. After almost ten years and the efforts of tens of thousands of people, we’d made it. I was finally able to relax and enjoy the Games with my family.”

It’s been ten years since the Games. What’s your verdict on the legacy of London 2012?

“It is clear that the overall improvement and transformation of East London is anchored in the original premise for the Games: the delivery of the Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park; rewilding of the Lea River; extended public transport networks and connectivity; new social infrastructure; three new communities and job creation focussed on innovation and high tech, with programmes supporting local start-ups as well as major corporate inward investors to Stratford and Hackney.”

BH: “While there have been many successes, it is important to acknowledge the challenges that remain. As with many, if not all, large scale regeneration schemes, financial success has not been shared evenly – for every data set that illustrates rising land and house values as increasing equity for exiting residents, there are clear indications that gentrification is pricing local families out of markets and this has not been balanced by the new developments having limited truly affordable housing.

Walking through the park though, it is evident that the transformation has triggered the ability to deliver economic, cultural, and social value and that has been reinforced by the new cultural quarter at Stratford Waterfront (East Bank) and the success of Here East (in the former International Broadcast Centre).”

“Ultimately, it is hard to imagine that the scale of transformation could have been achieved without London 2012. The Olympic and Paralympic Games are often referred to as ‘the greatest show on Earth’. Not only were the London Games our version of this ‘greatest show’, but as masterplanners, I truly believe that we succeeded in our job of creating the opportunities for positive change to take place.”

AECOM, leading multi-disciplinary teams drawn from the base to the London and international design and technical talent, has been at the forefront of planning and delivering the facilities and infrastructure for the London 2012 Games and the associated long-term legacy of the Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park, as the centrepiece of the regeneration of the Lower Lea Valley in East London. Beginning in 2003 supporting the regeneration case for the bid, the AECOM consortium has encompassed multi-disciplinary masterplanning for the entire development within the Olympic Park, securing planning permissions, compulsory purchase of land by public sector agencies and planning policy development.

The masterplanning consortium comprised: AECOM (originally EDAW), Allies & Morrison and Buro Happold along with Hargreaves Associates, Foreign Office Architects, HOK Sport (latterly Populus), Symonds, KCAP, Camlin Lonsdale, Beyond Green, JMP Health Consulting, Maccreanor Lavington Architects, WWM Architects, Vogt and Arup.

The post The catalyst for change: how we helped London win the bid for the 2012 Summer Olympic and Paralympic Games appeared first on Without Limits.

]]>The post Five key things London 2012 taught us about successful placemaking appeared first on Without Limits.

]]>A decade after the London 2012 Summer Olympic and Paralympic Games and it’s a good time for reflection on the legacy for East London and the capital as a whole.

While it would be hard to deny that the Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park (QEOP) and its surrounding development has failed to clear certain hurdles that often stand in the way of success on large regeneration schemes, it is clear that the overall improvement and transformation of East London is still anchored in the original premise for the Games: the delivery of the Park; rewilding of the Lea River; extended public transport networks; new social infrastructure; new housing (although the low levels of truly affordable housing is a disappointment given the original vision) and job creation in innovative and creative industries.

AECOM led the masterplanning consortium of designers, planners, engineers and engagement specialists for the entire scheme including games-time mode and planning for legacy build-out.

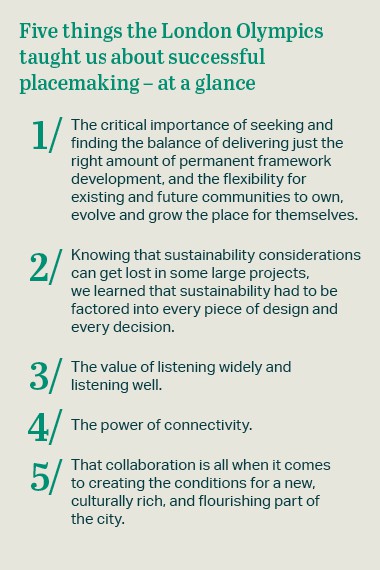

Here are five key things we learned along the way.

1/ Flexibility for the future

In masterplanning the QEOP and its legacy – as in any major project – planning for an unknown future is about creating a framework of possibilities. Flexibility has been key to the ongoing evolution from a post-industrial river valley to the setting for a global event and now the QEOP and its developments.

At this scale of development, flexibility comes in many guises. Our job was to create the opportunities for change to take place, for example designing games venues and facilities with a different future use in mind or enabling the planned Stratford Waterfront residential neighbourhood to be reimagined as the new cultural quarter.

“Our job was to create the opportunities for change to take place.”

Ultimately, we learned about the critical importance of seeking and finding the balance of delivering just the right amount of permanent framework development within a robust masterplan, flexible planning permissions and environmental assessments, which offer the opportunity for existing and future communities to own, evolve and grow the place for themselves.

2/Greenest games

The sustainability and environmental story of the games and park can be read at different scales.

At a micro level, the innovative biodiversity action plan ensured that detailed attention was paid to protecting and enhancing the habitats of the smallest animals and plants, while at the macro level, the legacy for London was a brand new, large-scale, accessible, high-quality public park.

A valuable part of the green and blue infrastructure of the city, the public park certainly demonstrated its value during the coronavirus pandemic.

Knowing that sustainability considerations can get lost in some large projects, we learned that sustainability had to be factored into every piece of design and every decision from the specification of building materials; the careful planning of bridges and roads; utilities; flood management; and the fact that all spectators (and most future residents and visitors) arrived on foot, by bicycle or by public transport.

3/Power to the people

The best lesson learned here was in listening widely and listening well. This was enabled by embedding a stakeholder engagement team with the planning and design teams, a fully integrated approach that today would be called co-creation. There was a culture of engagement and listening that became everyone’s responsibility.

In listening widely, we engaged with the broadest stakeholder groups from local residents and businesses, school children, sporting bodies and to local and city authority councillors. We heard about people’s concerns, but also their hopes, and tried to incorporate as many of their ideas as possible. The process and conversations meant we were able to develop a mutual understanding of what was possible.

Engagement is as important now as it was at the time of the Games as longstanding – and new -residents begin to own this new part of London. Efforts to embed QEOP in the local area so that benefits are more widely spread must continue.

4/Joined-up places

Connections within, across and around the park, and its integration into the fabric of the broader capital and beyond, have been critical to its success. The planning process sought to embed a network of movement, providing multiple ways for people to explore and evolve new routes, connecting people to employment and leisure opportunities. This has also stimulated organic development particularly in those areas which fringe the QEOP which have transformed into thriving new districts.

We have learned about the power of connectivity whether it’s by path or cycle way, bus routes or rail services. We are already seeing how opportunities in places like Hackney Wick or Fish Island can be opened up by a bridge in the right place, or an interesting intersection created by connections that facilitate access and movement, and that, in turn, sparks investment.

5/Stronger together

Our work was about making a place for people, so it was critical that the process had a very human dimension. This included fostering the collaboration of four host boroughs, transport agencies, local and regional government and the mayor, communities and latterly the London Legacy Development Corporation.

Collaboration also included co-locating planning and design teams from many practices, sharing offices and sharing ideas for the best solutions, enjoying the discussions and visits… all working together for the same purpose, to the same deadline for a great sense of shared endeavour.

We learned that collaboration is all when it comes to creating the conditions for a new, culturally rich and flourishing part of the city.

AECOM, leading multi-disciplinary teams drawn from the base to the London and international design and technical talent, has been at the forefront of planning and delivering the facilities and infrastructure for the London 2012 Games and the associated long-term legacy of the Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park, as the centrepiece of the regeneration of the Lower Lea Valley in East London. Beginning in 2003 supporting the regeneration case for the bid, the AECOM consortium has encompassed multi-disciplinary masterplanning for the entire development within the Olympic Park, securing planning permissions, compulsory purchase of land by public sector agencies and planning policy development.

The masterplanning consortium comprised: AECOM (originally EDAW), Allies & Morrison and Buro Happold along with Hargreaves Associates, Foreign Office Architects, HOK Sport (latterly Populus), Symonds, KCAP, Camlin Lonsdale, Beyond Green, JMP Health Consulting, Maccreanor Lavington Architects, WWM Architects, Vogt and Arup.

The post Five key things London 2012 taught us about successful placemaking appeared first on Without Limits.

]]>The post Performing better: concert halls costs appeared first on Without Limits.

]]>Concert halls form an important part of the cultural fabric of cities across the world. But they are complex to design and build, often costing more and taking longer to complete than planned, leaving clients with costly project overruns, and difficulties gaining funding.

Architecturally, concert halls are often ‘world class’ and designed according to international acoustic standards. Across Europe, government funding cuts mean there is also a growing requirement for them to be multi-functional performance spaces, capable of staging ballets and international orchestras to hosting corporate events, often impacting on the authenticity of their design and of the audience experience, leading to even greater cost considerations beyond more traditional concert hall builds.

We’ve identified some key design, procurement and construction considerations and costs that should be considered as part of any successful new-build concert hall project.

Design

Maximising the listener experience is a priority, making acoustics and design of the auditorium — along with front and back of house, which together typically take up 50 per cent of the space inside — critical design considerations.

Procurement

Preferred procurement options should be considered early on in concert hall projects to ensue compliance with funders and should align with local market conditions, while procurement strategies should ensure risk is split appropriately between client and contractor.

Construction

Concert hall construction typically represents 50- 60 per cent of total project expenditure, with auditorium and rehearsal spaces often the most costly areas to fit out.

To understand the many costs involved, we’ve examined these considerations in depth to create a cost model based on a new-build, international standard, 2,000-seat concert hall on a brownfield site in London with a gross floor area of 18,000m2.

Download here

The post Performing better: concert halls costs appeared first on Without Limits.

]]>The post Cultural buildings: a city’s ‘art and soul’ appeared first on Without Limits.

]]>Despite living in an ‘always on’ world where smart phones and social media offer connections at the tip of our fingers, many still prefer to look past their ‘friends’, ‘followers’ and online ‘circles’ in search of more ‘real’ community experiences.

In the real world, cultural infrastructure assets shape a city’s sense of community, leading to human interaction and experience that the virtual world simply cannot offer.

How these assets are designed and integrated into a city’s landscape also plays a role in the quality of life enjoyed by residents and the capacity of a city to attract visitors.

AECOM’s Arts & Culture sector lead Annette Pitman believes cultural assets are intrinsic to a city’s identity, referencing Hobart’s Museum of Old & New Art (MONA) and Bilbao’s Guggenheim museum as cultural destinations that have become synonymous with the cities in which they reside.

“Cultural assets have the special ability to cut through social boundaries, disregarding class, age and education,” she explains.

“We have Arts Centre Melbourne, the National Gallery of Victoria, the State Library to name just a few – anyone can go into these places, walk around, look at their amazing art collections and feel part of something much bigger than themselves.”

Buildings that engage and nourish

The Seattle Central Library, designed by influential Dutch architect Rem Koolhaas, is a cultural asset that reflects the diverse needs of its community.

Its design embraces the notion that a library can be more than just a place to read and borrow books. Knowledge and discovery intersect in this egalitarian community haven that also provides an escape for a child in difficult circumstances at home, and a source of warmth and comfort for Seattle’s homeless in winter.

As a multi-purpose civic icon, the Seattle Central Library quickly established itself as one of the USA’s leading examples of cultural infrastructure, attracting 2.3 million people through its doors in its first year, of which an estimated 30 percent were not from the Seattle area.

A young heArtbeat

Back in Melbourne, Pitman applies her love of the arts and passion for creating buildings that engage and challenge to her work on the revitalisation of Hamer Hall and Arts Centre Melbourne.

Constructed just 30 years ago, the Arts Centre Melbourne’s original designers – leading Australian architect Sir Roy Grounds and Academy Award winning costume and production designer John Truscott – wanted to transport visitors to a different world.

Now, as Melbourne continues its evolution as a world city, the Arts Centre’s revitalisation underlines the importance of it remaining both a destination of choice, and an asset that can engage and nourish.

AECOM’s advisory arm is conducting the economic analysis for the building, while Pitman’s team is project managing the development of a masterplan and business case for the centre’s redevelopment.

“As with all cultural infrastructure projects, we need to consider what an arts centre of the future will look like 30 years from now,” says Pitman.

“What do we envision its role in the city will be, and how can we give the institution the tools required to make that all-important connection with the community?”

“It is essential that the right decisions are made now to ensure the centre remains a valuable cultural and community asset in the future.”

In 2015, more than 1.2 million people enjoyed performances at Arts Centre Melbourne venues, including almost 80,000 students. An estimated 227,000 people were also reached via 1,877 education and engagement programs, numbers illustrating how Arts Centre Melbourne feeds engagement and enriches the city.

Civic pride comes from inhabitants identifying with the nuances that give a place its vitality. The many intricacies – the light and shade – cast by cultural infrastructure are pivotal to creating and sustaining that relationship between a place and its people – that bond between the creative and the concrete that is the Art and Soul of any city.

The post Cultural buildings: a city’s ‘art and soul’ appeared first on Without Limits.

]]>The post Money tree: the green space payoff appeared first on Without Limits.

]]>Environmentalists have long championed the benefits of green space, and now, with greater support from corporate Australia and a plethora of concerned higher-learning centres and community groups, it appears the commitment to a greener, healthier future has become mainstream.

Those driving the 202020 Vision are flush with evidence to support their push for 20 percent more green spaces in urban areas by 2020.

A well-placed park can enhance the well being of a community by encouraging physical activity and helping build social connections. Trees remove pollution and improve air quality. Rainwater gardens alongside roads can filter runoff from stormwater, improving the quality of groundwater. Trees throw shade, which reduces the ‘heat island effect’ and keeps our cities cooler. Urban forestry increases native flora and fauna and supports ecosystems within.

There are a myriad of benefits that support the introduction of more green space – but what of the economic rewards?

Perth-based AECOM strategic advice consultant Rachel Thorpe believes green urban space can deliver an immediate economic windfall for cities.

“Research shows customers prefer a shopping strip featuring shade and green,” she explains.

“They tend to stay longer and shop more, which increases retail yield.”

In addition to creating an environment where shoppers are more likely to spend, businesses can also create more appealing work environments for their staff through providing facilities that include green features.

“Working in a building that contains green infrastructure can improve a person’s mental health, reduce stress and fatigue and boost productivity, leading to less absenteeism and a greater return on human investment,” she said.

The same is true in terms of traditional healthcare, with many new hospitals acknowledging the healing benefits of green spaces by incorporating them into innovative designs, indirectly resulting in shorter stays and less burden on the public system.

Combined, these benefits enhance a community’s resilience and position it for prosperity with a healthy, happy workforce.

Time to act

From a health policy and water policy standpoint, the time is now to promote understanding of the economic benefits of a robust green infrastructure program.

Mrs Thorpe cites Perth as a prime example of why.

“Western Australia is at a critical point with regards to losing its green open space because of the lack of formalised understanding of the value, in a time of increased urban density,” she said.

“It’s vital that we can clearly compare the particular economic value to the community of a grey infrastructure asset such as a bridge or a road to the value of a green open space, like a park or a vertical garden.”

While arguably less visible, the economic flow-on effects from increased green space are nonetheless incentivising participation from government and private sector participants. In Western Australia, the push is on to look beyond anecdotal evidence and establish a matrix to put a dollar value on ‘going green’.

“What we need is a true, tried-and-tested framework that places a value on green infrastructure, so that policy makers who hold the purse strings can clearly understand the associated community benefits,” she said.

“Only when we have such a system will we be able to educate people about why it’s economically vital that we protect and continue to create more green spaces in urban areas.”

AECOM has applied for support through the ‘Green Cities fund’ run by Horticulture Innovation Australia to produce the matrix and the framework to be able to put a value on green open space.

The post Money tree: the green space payoff appeared first on Without Limits.

]]>The post Why the future lies beneath our feet appeared first on Without Limits.

]]>Dr John Endicott, AECOM Asia Fellow, advisor to the Hong Kong and Singaporean planning authorities argues that underground space is vastly underutilised, and is an area of enormous, and unrealised potential.

Boasting more than 40 years of experience covering over 100 major underground projects globally, he says there are many opportunities to excavate and explore underground to meet the seemingly insatiable demands of our ever-growing population.

Just scratching the surface

Planning decisions made a generation ago are struggling to cope with the demands of today’s increasingly dense cities. The aspirational quarter acre block in the leafy suburbs disconnected from public transport appears wasteful by today’s standards.

Once we get past the first few metres of foundations and utilities, there is almost unlimited, virgin, available space. But safe and effective excavation depends on the stability of the roof and the side walls. Solid, strong rock such as the igneous granite under Hong Kong or the Hawkesbury sandstone buried under Sydney streets provides excellent foundations. These rocks can support caverns with spans of 27 metres, and sometimes more depending on the condition of the rock.

Global advances

At over 91 metres long and nine stories high, the Gjøvik Olympic Hall in Norway claims the title of the world’s largest excavated occupied cavern. This underground hall was constructed within the local gneiss metamorphic rock with the addition of applied rock mechanics.

It has a capacity of over 5,000 and hosted ice hockey games for the 1994 Lillehammer Winter Olympics. It is now a multi-use arena hosting a variety of sports, conferences and exhibitions within a climate-controlled, centrally-located, safe environment.

In Asia, Hong Kong and Singapore have leveraged their underground space to preserve their limited and precious aboveground amenities and common space.

The island cities’ underground railway stations are linked to retail, entertainment and sporting facilities to provide streamlined interconnectivity, improving sustainability and slashing commuting times.

It is possible in both Hong Kong and Singapore to commute, work, shop, eat out and visit entertainment facilities entirely indoors and mostly underground. Temperature-controlled environments will become increasingly attractive with climate change and growing extremes in weather.

Creating the space

While many of us may think of underground spaces as being dark, damp and unsafe this is not the reality. With effective planning, expert geotechnical analysis, modern ventilation and a creative approach to place-making, caverns can be safer and more pleasant environments than aboveground office towers or shopping malls, allowing our open space to be used for parks, playgrounds and the natural environment.

The unrealised potential of underground space has the power to create a new, 24/7, climate-controlled metropolis without expanding our footprint, increasing congestion or spiralling commuting times. Our future can include concert halls; major sporting facilities; efficient and interconnected shopping, transport and work networks that will grow our cities’ capabilities.

All we need to do is look down and start digging!

The post Why the future lies beneath our feet appeared first on Without Limits.

]]>The post The long, long game appeared first on Without Limits.

]]>Within days of Germany taking home the 2014 FIFA World CupTM trophy, questions started raging about the future of the dozen shiny stadiums built and/or renovated for the 2014 World Cup. Observers speculated that at least four of the Brazilian venues will find it tough to fill seats and meet the massive upkeep costs. Already architects have produced intriguing images of the stadiums transformed into much-needed housing.

Brazil is certainly not alone in splashing out on host venues which, unfortunately, could have the potential to be ghost venues. Nevertheless, the development of stadiums for world sporting events, can and does, deliver multiple benefits — improved infrastructure, and elite facilities for national athletes as well as an enhanced national pride. Success is about making the most of these benefits for the long run.

After the crowds go home

When major events come to an end and the international fans go home, the spectator profile of the stadiums immediately changes from sports tourists to local residents. Operators or public bodies inherit the stadium and the reality of running costs hit public pockets. Unless occupation is transferred to an anchor tenant such as a local top-league football team, the prospect of high ongoing maintenance and utility costs is daunting.

The legacy optimum

In our work delivering stadium economic feasibility studies for world-event hosts, our first task is always to identify the optimum capacity in the legacy phase (reduced from world event staging). This is about taking a realistic view of potential demand throughout the year. This can be for a single sport (i.e. football) or a multi-sport facility. The concept is essentially the same. How can we make the stadium work economically? And what will make it, inherently, part of the local community? This will, in turn, make it part of the surrounding city, country or regional social and economic infrastructure.

In our work delivering stadium economic feasibility studies for world-event hosts, our first task is always to identify the optimum capacity in the legacy phase (reduced from world event staging). This is about taking a realistic view of potential demand throughout the year. This can be for a single sport (i.e. football) or a multi-sport facility. The concept is essentially the same. How can we make the stadium work economically? And what will make it, inherently, part of the local community? This will, in turn, make it part of the surrounding city, country or regional social and economic infrastructure.

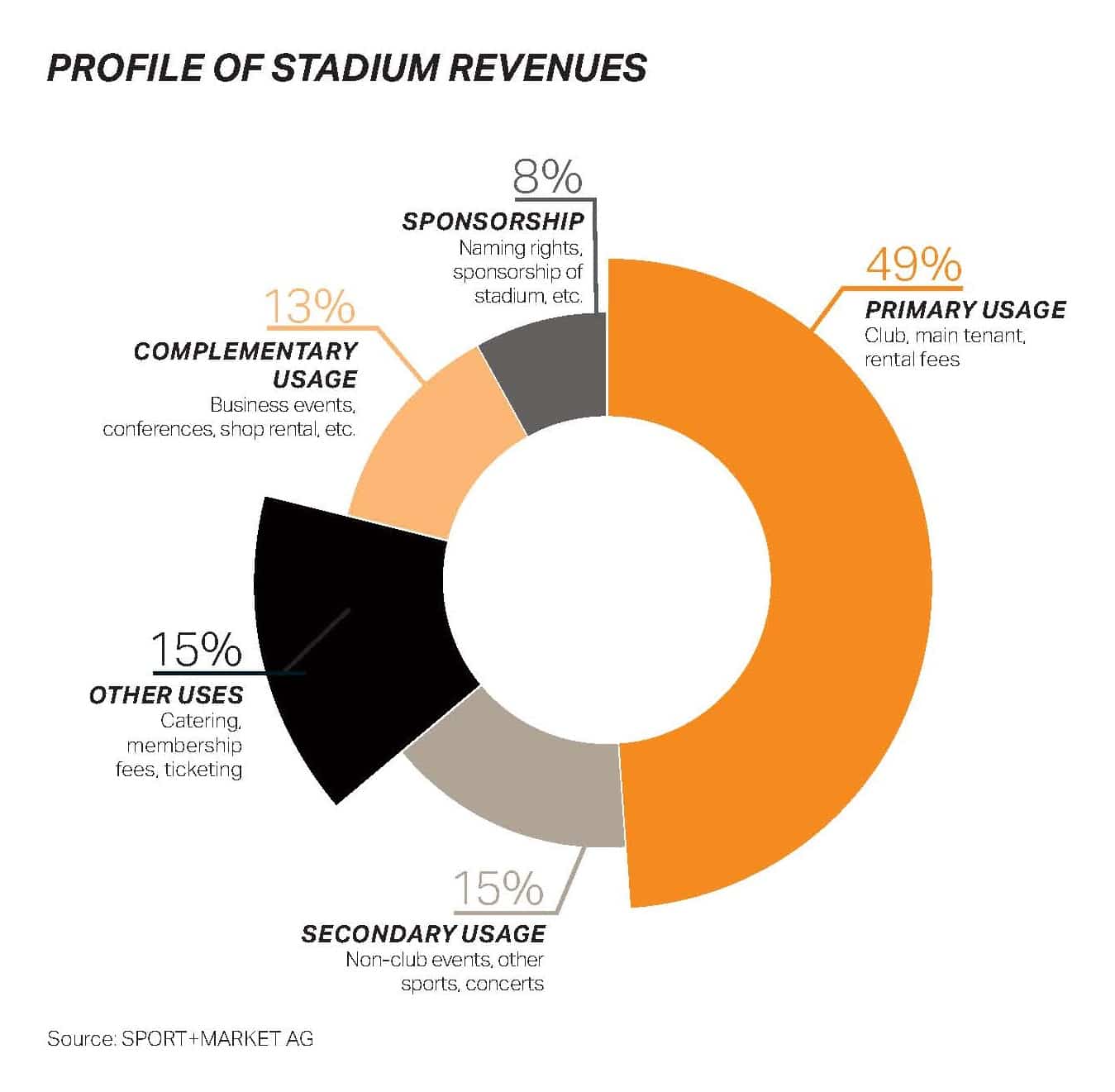

Revenue sources

In a recent survey of 70 stadiums (located around the world) it was revealed that almost half of the stadium revenues come from primary usage. Additional income comes from secondary sources, such as non-club events, concerts, catering and venue hires.

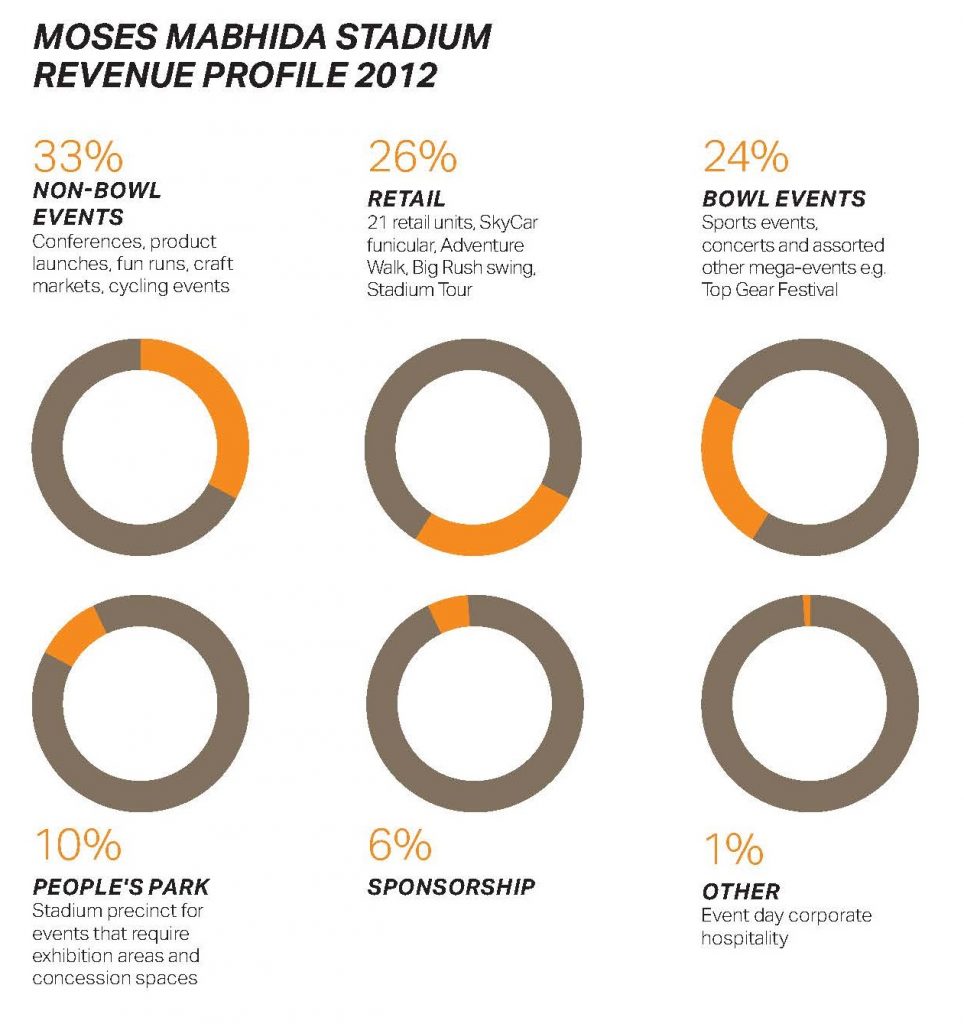

This clearly outlines the opportunity and need for stadium operators to diversify their revenue streams. Without anchor tenants this can be tough, but is not impossible. For example, the Moses Mabhida Stadium in Durban, South Africa, a 56,000-seat stadium purpose-built for the 2010 FIFA World CupTM, is gradually reaching breakeven point. Without an anchor tenant, this has been achieved through innovative design that made the stadium a tourist attraction — with a SkyCar and Viewing Platform for unparalleled, 360 degree views of the city — and by hosting a variety of bowl and non-bowl events including the hugely successful Top Gear Festival.

Defining the commercial viability and use

If offering and designing for diverse use is invaluable to the long-term commercial viability of stadiums, we should also be, at the planning stage, considering the wider options of sporting facilities either as standalone venues or as part of a stadium complex development.

Arenas, for example, provide the opportunity for a mix of uses, all year round, encompassing major sporting events, music tours, venue hire and

corporate hospitality.

As standalone venues or as part of larger stadium complexes, the design and development of arenas becomes equally important. And their city-center locations link to the wider benefits of sport development: local pride, community engagement, health and wellbeing, and regular positive tourist income.

The First Direct Arena in Leeds, U.K., as Tele 2 in Stockholm, Sweden which opened in 2013 and includes entertainment space, and associated facilities which meet FIFA and UEFA requirements.

Whatever the ambitions for stadium and arena development, planning and designing with long-term commercial and community viability in mind will transform any investment. The inclusion of a diverse range of uses and activities that facilitate the venue operating non-stop throughout the year will have a significant positive impact on project cashflow and the scheme’s financial return profile.

The post The long, long game appeared first on Without Limits.

]]>The post Destination sport appeared first on Without Limits.

]]>When it comes to sport, few things compare to being part of the excitement and roar of a crowd, whether you’re pitch, pool or track side.

These days, an increasing number of people are travelling abroad to watch and cheer on their favourite team or athlete. In fact, sport tourism is one of the fastest-growing sectors in global tourism.

Creating positive legacies

So-called ‘mega’ events such as the Olympic and Paralympic Games, FIFA World Cup and Commonwealth Games attract new visitors to a city or region and can generate positive legacies such as local urban regeneration and employment. However, despite the International Olympic Committee’s 2014 reforms to make bidding for the Olympic Games more affordable, only a relatively small group of cities have the capability and funds to bid for and host mega events. Even then, they often struggle to capture the public’s imagination and support needed to see through the process. Hamburg’s bid to host the 2024 Olympics for example collapsed after most of the city’s residents voted against the multi-billion Euro project in a referendum.

The significance of smaller

Outside of the mega sport event circuit, an increasing number of cities and towns are recognising that bigger is not necessarily better. A balanced portfolio of smaller or lower profile sport and other events not only require less public investment to get off the ground, but have the potential to attract a steady flow of visitors, generate local and international publicity and interest, boost the local economy, strengthen community spirit and reinforce their image and reputation. This is especially the case for smaller economies with strong natural or existing built assets and good accessibility looking to establish themselves on the tourist map.

Look to your strengths

The Cayman Islands is one example. The British Overseas Territory has a population of less than 60,000, but in recent years it has hosted The Confederation of North, Central America and Caribbean Association Football youth soccer tournament, attracting 3,000 visitors to the island, while the Cayman Invitational Track event featuring Usain Bolt brought 110 coaches and athletes to the region, leading to 115 articles in international press, including ESPN and the BBC.

The Travel Activities and Motivations Survey (TAMS), which looks at the travel patterns of Americans and Canadians, suggests sport tourists are also more likely than your average tourist to attend festivals, concerts and live theatre during their stay — many of these attractions are already offered in established and emerging travel destinations throughout the world.

Arrive earlier, stay later

Generating the greatest benefits from smaller-scale sporting events lies not only in promoting the event itself, but giving sport tourists reasons to arrive at the destination earlier, stay later and spend more. To do this, tourism boards and authorities need to think strategically about travel packages and incentives and associated cultural programmes.Allocating the appropriate resources is another important factor. The City of Hamilton in Ontario, Canada, is a good case in point — in 2005 Tourism Hamilton adopted a Sport Tourism Action Plan and hired two full-time staff dedicated to driving sports tourism across the city. By making sports tourism a strategic priority, Hamilton held 136 sport events during 2006 and 2007, up 120 per cent on the previous year.

Strategies for success

What are some other key strategic considerations when planning and hosting small-scale sporting events to spur lasting, positive legacies in host communities?

Build on what you’ve already got

Sporting events provide great opportunities for destinations to promote and strengthen their existing natural and built tourist attractions. By doing so, sports tourists will have good reason to stay longer and explore the local area.

We have been looking at ways to increase tourism during off-peak and shoulder (between peak and offpeak) months at one of the world’s leading superyacht destinations, Porto Montenegro, off the Bay of Kotor in Tivat, Montenegro, by creating high-profile invitational sport events such as triathlons and adventure races that capitalise on the dramatic coastal and mountain landscape.

Choose the right sport

Success will depend on how well the chosen sport or activities suit the destination’s demographic, natural setting and local activities. Queenstown in New Zealand has successfully capitalised on its adventure tourism credential to develop the American Express Queenstown Winter Festival, attracting over 45,000 people to this annual event.

Think off-peak

Sports are a year-round pastime, but an effective sport tourism strategy should particularly look to promote sporting events during the slower tourism periods when accommodation is more readily available and more affordable.

Package and incentivise

Creating travel packages makes a destination more attractive to sport fans and participants. Here, it works well when sport and tourism bodies work together to create attractive packages and incentives, such as discounted hotel rates for particular sport events.

Creating travel packages makes a destination more attractive to sport fans and participants. Here, it works well when sport and tourism bodies work together to create attractive packages and incentives, such as discounted hotel rates for particular sport events.The Malta Tourism Authority and the Malta Sports Council work to increase tourism during off-peak and shoulder months by offering subsidies to the National Sports Association per number of hotel beds booked during sports events. This incentive generated 60,000 additional ‘bednights’ over the initial three-year period.

The Malta Tourism Authority and the Malta Sports Council work to increase tourism during off-peak and shoulder months by offering subsidies to the National Sports Association per number of hotel beds booked during sports events. This incentive generated 60,000 additional ‘bednights’ over the initial three-year period.

Partner up

It takes a multitude of agencies and organisations, from tourism boards to volunteer groups, to effectively plan and host any scale of sport event or any tourism event for that matter — each with their own objectives and capabilities. Creating a dedicated stakeholder group or bidding organisation can help promote collaborative working and align different agendas.

Think local

It’s a good idea to get local businesses involved from the start — not only will visitors be staying in their hotels and eating at their restaurants, but businesses can offer insight into which events might be best suited to the local services on offer. Many events now run a concurrent business club in association with the local chamber of commerce.

The post Destination sport appeared first on Without Limits.

]]>The post SAINT comes marching in appeared first on Without Limits.

]]>Just like following a favorite team or player, investment in stadiums and arenas has always involved the possibility of euphoric success or the failure to achieve full potential. Of course success can be secured in many ways, and one route to making fast, informed decisions and reducing the risk of failure, is the new online stadium and arena investment tool called SAINT.

This kit enables stadium and arena owners, their investors, and project teams to get an early indication and fine tune the viability of a project. It helps balance operational and capital demands, and highlights the opportunities to inform design and improve the facility’s long-term use and revenue. Taking in the whole 360 degree scheme vision, key areas explored in the calculations include design, cost, program, operations and finance. SAINT allows for seamless integration of processes that were once linear and disconnected: market analysis, cost and revenue projections and design synthesis.

SAINT provides access to relevant design, cost, program and operations data that can be analyzed to help guide the development of the concept scheme, inform future operational impact and ultimately assess overall viability

At the heart of this software is robust industry data from Global Unite, AECOM’s bespoke international cost benchmarking and project performance indicator database. By linking to this data the tool can benchmark a vast range of development scenarios, from the numbers of seats and the type of roof design to whether to outsource catering. It calculates potential revenue and provides a clear view of the cost, value, and payback of any major stadium or arena development, even across wider masterplans incorporating commercial, residential, leisure and retail mixed use.

SAINT takes into account a number of factors including:

- Capacity

- General admission/corporate split

- Optimum program

- Total size (square meters)

- Structure and design

- Quality of finish and fit out

- Programme duration

- Construction costs

- Development costs

- Operating and utility costs

- Maintenance costs

- Lifecycle costs

- Matchday revenue

- Non-matchday revenue

- Sensitivity analysis appraisal

SAINT enables stadium and arena owners to get an early indication of the viability of a project

The post SAINT comes marching in appeared first on Without Limits.

]]>The post Debunking millennial myths appeared first on Without Limits.

]]>Anyone who has seen a college football or basketball game knows how important the student section can be — those free throw shots framed by densely packed students wildly waving their arms to distract, or football time-outs with students sporting body paint and dancing with the band.

Student sections are a point of pride for college athletic departments. Yet last summer, curious stories started appearing up in the mainstream American press about declining attendance at college games, mostly football, but at basketball and other sports as well. The decline has affected all sports, regions and types of school.

Commentators were quick to offer opinions for the reason for this decline. People prefer to stay at home and take advantage of the benefits televised sports offer, they said — replays, interviews, and exhaustive data about every play, goal and participant. Others suggested that sports events are too long for today’s distracted youth or that young people have lost interest in sports altogether.

Bucking the trend

The University of Texas at Austin (UTA) Athletic Department wanted to buck this trend by reversing the decline and building an exciting, compelling student section. If successful, this would elevate the mood of UTA’s entire arena, making game days more exciting and providing a better spectacle for televised shows, while also building a future donor base from current student attendees.

UTA asked AECOM Strategy+ and its sports team to help — a team that conducts user research around the world in order to build better sporting venues, museums, workplaces and cities.

Profiling your people

Working with UTA, we spent five months studying the problem, combining hands-on engagement with social media research to build a comprehensive picture of what students really want from sports events.

We hung out with students on game day, interviewing 200 of them as they arrived, watched the game and partied, and conducted exit gate interviews to find out why fans left early.

We also analyzed the demographics of UTA ticket purchases over the last four years to identify who bought tickets, who went to the game and how often. We investigated how fans used social media to discover, plan and share events. And we ran workshops where we encouraged students to create an ideal student seating section.

All this information helped us create ‘psychographic’ profiles of UTA audiences — detailed breakdowns of their preferences and attitudes, including what drives them, how they feel about sports, and what type of experience would appeal to them.

Analysis, not myths

Our research gave us and UTA lots to think about. And it shone a light on some of the enduring myths of student sports attendance in the U.S. today. No one had questioned these assumptions until now, but our in-depth analysis found that there was very little truth in them.

Our approach helped UTA get to the heart of the problem. Right now, we are working with the department to put some solid, actionable recommendations together, based on this research, to help UTA nurture a whole new generation of fans.

There is a wider application for this research too. Student attendances are declining in the U.S., in all sports. Every sport is different and every college is different, but by adopting a rational, evidence based method and a structured process, clubs and colleges will be in a good position to halt that decline.

UTA: Getting to the heart of the problem

Myth #1: The in-home viewing experience is the biggest competitor

The myth: There is a strong feeling in the press and the industry that the in-home viewing experience is the biggest competitor to the live event. Big screens and a constant stream of stats and data mean young people can get a thrilling fan experience from the comfort of their own homes.

The reality: Fans continually mentioned the experience of cheering with 100,000 other people, the energy and excitement of being at the live event. The social aspect of seeing friends and sharing the event with them is incredibly important, and the in-home viewing experience can’t compete with the immediacy and energy in the same way.

Recommendation: Rather than competing with the home viewing experience athletic departments should focus on what makes attending in person so exciting — the crowds, the live entertainment, in-stadium replays. Stadium designs should support that social environment.

Myth #2: In-stadium technology is an arms race

The myth: Many athletic departments believe super-fast Wi-Fi and other leading technology is essential to keep student fans interested during the game. Some are working very hard to improve wireless within stadiums and arenas, sometimes at significant cost and disruption.

The reality: Much of this is the result of previous, poorly designed research. Many ticket buyer surveys ask users if they would want better, faster wireless, and if it would influence their purchasing decision. It’s a leading question and the answer is almost always yes.

Yet more subtle, open-ended questions about what fans actually want revealed that better technology isn’t the significant differentiator everyone thought. For example, UTA’s stadium has a difficult wireless reception in the bowl, but, no students said that influenced their decision to attend or when to attend.

Recommendation: Don’t bust your budget installing the latest, fastest Wi-Fi. Decide on an acceptable level of connectivity and use it to drive grassroots marketing. Millennials love events that are ‘shareworthy’, so they can post photos and updates to social media. In essence, this is great, free advertising for your club or event.

Myth #3: Sporting events are too long

The myth: There is a fear that this generation just doesn’t like sports or can’t devote an entire day to a game, since they have so many other things competing for their time.

The reality: To test this hypothesis, we examined other events that are meaningful and popular with these students. In particular, the popularity of multi-day music festivals confounded our assumptions about attention span, physical comfort and spending. This generation does have time and money to spend, but what sets music festivals apart is the freedom to create an individual experience — they pick which bands to see, which friends to meet up with and how to spend their time.

Recommendation: Sports events should allow fans to enjoy things in different ways. For students that didn’t necessarily grow up loving American Football, this might include a ‘football 101’ class during the game or more statistics and information about the players and the plays. For socially driven students, this would include general admission seating sections, or sections without seats that would allow students to wander and mingle.

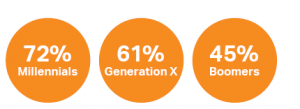

More experience: Less stuff

Percentage of groups who increasingly want novel experiences

IWT Intelligence, 2013<

Myth #4: Millenials just don’t care about sports

The myth: Not only are sports events too long, they’re not even very interesting, compared to the myriad of other distractions and entertainment available to Millennials. This is the biggest myth of all.

The reality: Throughout our research, students were very clear about the appeal of sports — it’s about identity, social connection, meaningful affiliation, fun, social sharing and excitement. They are far from disinterested — but there is a significant gap between their interests and the viewing experience currently offered by most sporting events.

Recommendations: A great thing about this generation is that they are more than willing to help bridge this gap, to help design solutions that create a better and more compelling experience, one that will turn them into lifelong, diehard fans.

More than giveaways or promotions, Millennials want their teams to provide access — to players, coaches and the field. For athletics departments, this process of asking provides that access while creating meaningful connections to student fans, which is critical.

Fewer Fanatics, more neophytes

Since 1994, 12.3 percent fewer 18-34 year old men consider themselves avid sports fans.*

*Source: Sports Business Daily, 2014

The post Debunking millennial myths appeared first on Without Limits.

]]>The post Testing, testing, 1, 2, 3 appeared first on Without Limits.

]]>No one would doubt that major sports events like the Olympics and the FIFA World CupTM provide a near unbeatable mix of sporting excellence, excitement and glamour. Yet after the glitz of the closing ceremony has faded, the hard work begins on running these iconic stadia for the decades to come.

This operations phase, however, is not simply a case of handing over the keys to a management company. A clear concept for how to operate a stadium is needed from the very beginning of the project, otherwise running the venue may not be as smooth as expected.

Timing is important, particularly as construction completion approaches. Operators should start setting up their basic management structures at least 18 months before construction completes, to be able to develop event schedules and book artists, secure sponsorship deals and market premium offers.

Above all, it is a professionally organized programme of test events that enable operators to evaluate everything about the new venue — management, staff, service providers, emergency services and even spectators — and ensure these essential individual parts lock together to provide the high-quality experience fans expect.

Trial, and no error: making your test a success

Test events are challenging situations. There are still many uncertainties and risks arising from occupying a new venue with thousands of spectators for the first time. There is also great public interest and high expectations.

Test events are challenging situations. There are still many uncertainties and risks arising from occupying a new venue with thousands of spectators for the first time. There is also great public interest and high expectations.

But above all, a test is an opportunity – a chance to showcase the new facility to the local community and city. Here are a few rules to guide you to success.

Construction completion

Make sure the building is completed, commissioned and handed over before the test event. Make sure you have all of your paperwork in order. An occupation certificate is an obvious requirement.

So-called ‘substantial completion’, where most of the work has been done, but there is some still to do, might seem like an easier option, but this may end up being riskier. The operator fit-out should also be completed. Typically, this overlaps with the final stages of construction, so it needs to be managed carefully.

Keep in mind that most areas of the stadium will be used during the test event so there needs to be a clear differentiation between construction snags and wear and tear resulting from the test events. Encourage everyone involved in the test event to treat the stadium with respect to maintain its pristine condition.

Start thinking about maintenance contracts and technical facilities management when signing the construction contract to ensure the most effective handover and smooth technical operation.

Operation

Operator tenders and contracts have to be finalised long before test events. This is usually a lengthy and complex process, governing who should run the facility, how much control city authorities can exert, key performance indicators, cost/revenue splits and so on. The stadium owner’s manual should include very detailed operating procedures, describing how the stadium will be run on an event day, how different work streams collaborate, and roles and responsibilities for each team member. The technical section must include as-built information in a format suitable for the facilities management team for events and regular maintenance. You will also need operational health and safety certificates, trading licenses for retail outlets and restaurants, occupational health certificates for the public and VIP catering, and building and public liability insurances. The focus of the final weeks running up to the test event should be on the event itself. Ensure every staff member has been trained and is familiar with their roles and responsibilities, whether they are permanent employees or casual staff.

Stakeholder coordination

Essential services like catering, cleaning waste management and event security are often outsourced and, if so, must have been procured prior the event to give teams the opportunity to familiarize themselves with the stadium. Emergency services should also be engaged early.

Events in the new stadium will have a significant impact on a city, so the city authorities should be prepared to make the most of the opportunity that a major new stadium offers. As well as technical aspects like transport and disaster management, this collaboration should include tourism campaigns, joint marketing activities.

Moses Mabhiba Stadium, Durban, South Africa

The Moses Mabhida Stadium in Durban, South Africa, was designed, delivered and operated by AECOM for the FIFA World Cup 2010 . A multi-purpose venue, it boasted a total capacity of 70,000 seats for the World Cup, scaled down to 56,000 seats post 2010.

. A multi-purpose venue, it boasted a total capacity of 70,000 seats for the World Cup, scaled down to 56,000 seats post 2010.

Here, Alf Oschatz reflects on how AECOM came to operate the stadium for three years after the 2010 tournament, and how the team made the most of the opportunity in occasionally challenging circumstances.

“We had been involved in the Moses Mabhida Stadium from the start, so we knew the project and city well. With six months of construction still to complete, Durban’s city authorities asked if we could take on the operator responsibility for the stadium until a long-term operator was found.

Our initial contract was for 18 months, including the tournament period, but we ended up having the term extended twice before handing it over to the city’s sports and recreation department.

It was incredibly important to us that the operational phase adopted the same high standards applied during design and construction. To do this we assembled a team of our project managers and engineers — experts in stadium construction —and partnered with a third-party event organiser for commercial management.

Finding the right commercial partners (sponsors and retail tenants) on time was a challenge from the get-go. Timescales were tight and regulations were complex. At times, it was a struggle.

The integration of technical staff and construction contractors in the maintenance team worked well. We had a good relationship with major stakeholders within the city council (transport, emergency services, city marketing and tourism) which we had developed during design and construction. It was a great team and we handled the challenges of test events well.

Resourcing other staff was, at first, tricky. There just wasn’t an existing talent pool to choose from. So we created our own. So, for example, we worked with local hotel schools to identify interested and capable individuals and trained them as premium area service staff.

It was a busy period, and, at times, hectic. Between practical completion and the kick-off for the opening World Cup match, we were managing and coordinating three different programmes; snagging, overlay installation for the tournament and the round the clock steady-state stadium operation.

We needed a solid, detailed understanding of these different elements and a balanced approach to delivery — not to mention even more exceptional project management skills than usual to keep all of these plates spinning!

But with focus and determination, we got there. We handed over a fully operational and tested stadium to FIFA for the 2010 World CupTM, and there were no technical or operational issues during the tournament. Then in 2013 we handed over the stadium again — this time, the handover was to the city of Durban, following three successful years of operation, and including a detailed operations manual and a fully trained staff team who knew the facility inside out. A great result.”

The post Testing, testing, 1, 2, 3 appeared first on Without Limits.

]]>The post Last but not least appeared first on Without Limits.

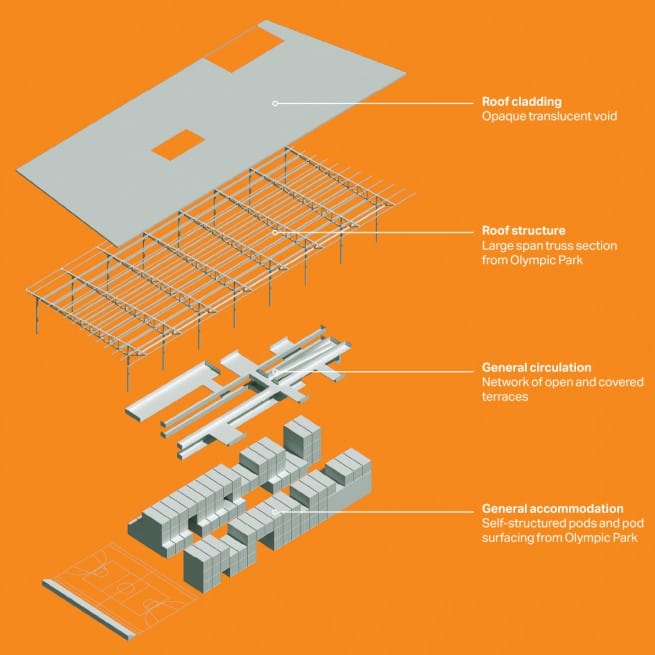

]]>Mention the words ‘overlay design’ to anyone involved in delivering an Olympic Games and, chances are, they will think of those busy final stages of the preparations when the temporary structures such as tents, cabins and scaffolding are installed, and the venues and infrastructure are made ready for the start of the competition.

To a certain extent, that is a fair picture. Yet these temporary structures and final construction details are just part — a critical part, admittedly — of the overlay architect’s job description. “Overlay design is much more than tents, toilets and temporary venues,” says Ana Loreto Vasquez. “It creates detailed plans for running the whole event and also ensures everyone who comes to see the Games has a once-in-a-lifetime experience.”

Good operational design

It is all about good operational design, says Vasquez. “We try to see things from the perspectives of everyone involved — the spectators, athletes, camera operators, the press, all of the client groups — and get the best result for all of them,” she explains.

This involves getting to grips with every part of the event. As well as understanding the governing body’s standards and guidelines, you need a detailed knowledge of the host city, the venues and the space, to figure out how it can accommodate those guidelines in the best way.

Why to start?

“Ideally, this should all be considered at the very beginning,” says Vasquez. “Starting your overlay design early means you can get to grips with all this, and optimize the people and resources you need.”

Overlay design teams can help even at the bid stage. Vasquez says that overlay specialists can support cities as they choose their venues and sites, help them shape the Games masterplan to make of the most of their infrastructure and provide the best backdrop for each sport.

However, it is really once the host city has been announced that overlay teams come into their own. “Our plans feed into almost every part of the Games,” says Vasquez. Overlay teams interact constantly with all the operational teams in a dynamic process, planning each venue and helping define an event’s operational plan.

Hands-on expertise

They work closely with transport and security, helping define the best strategy to support the mobility and safety of the Games. They help ensure procurement is cost effective. And, of course, they build the temporary elements and operate the event.

“A host city will make sure its Olympics are always a success,” adds Vasquez. “But hands-on overlay expertise can make getting there a whole lot smoother.”

Vasquez and her team have put together overlay programmes for several Olympic Games, as well as for other major sporting events. The team is currently involved in the some of the biggest sports events coming up in next few years.

A different scale

“An Olympics or Commonwealth Games has a different scale from other championships,” says Maria Canovas. “At any one time, there could be many different events happening at many multiple sports venues across a city. Things are also going on in the non-competition venues such as the Athlete’s Village, the International Broadcast Center, and the training venues, not to mention the logistics warehouses and transport hubs.”

Among all this activity, maintaining a joined-up spectator experience is critical. “You could have the best stadium, with the best technology, but if your train breaks down on the way there, it can ruin your day.”

This is why good overlay planning is so important. “Our overlay teams know the venues from the corridor level up,” Canovas explains. “They are the people who see the importance of how everything fits together, from the detail of a single room to the way an Olympic Park interacts with the rest of the city. We look at the whole picture.”

In short, overlay design helps ensure that the venues and site can successfully host the operation of an event.

Overlay design: A timeline

9 years before opening ceremony

The bid: From applicant to candidate

- Venue evaluation: Analyzing venues and sites for the feasibility study

- Masterplan support: Working with infrastructure, transport and security teams to choose the best venues and sites for sports and operations

- Bid Book preparation: Helping create detail answers to the international Olympic Committee questionnaire

- Legacy planning: Writing legacy briefs for venues and economic impact studies

4 years before opening ceremony

Phase 1: Scope and masterplan

- Building the team

- Venue briefs/requirements

- Scope definition/agreement

- Masterplan optimization

- Overlay block planning

- Budget preparation

- Integration with public works authorities on new venue designs

- Interface with stakeholders

- Strategic planning and programme development

3 years before opening ceremony

Phase 2: Planning and design

- Overlay design management: Covers all stages of the design process, taking it from block plan, through concept design, to schematic and detailed design

- Venue/scope lockdown

- Functional area specific drawings

- Venue operational planning

- Procurement

- Statutory consents including town planning and building control

- Engineering services design

1 year before opening ceremony

Phase 3: Delivery and installation

- Coordination of design, including overlay contractors drawings

- Design freeze

- Construction drawings

- Test events

- Overlay installation: Liaising with contractors and construction management support to ensure consistency and on-time delivery

- Site and venue management

After the games: Transition to legacy

- Assisting in the transition from event to legacy use. Ensuring that plans focus only those elements that are viable in legacy mode.

The post Last but not least appeared first on Without Limits.

]]>The post Your flexible friend appeared first on Without Limits.

]]>Building a new stadium or arena is a costly undertaking. Spectators and athletes alike demand the best facilities, and creating a venue that enhances the reputation of its home club or city rarely comes cheap. Yet long-term economic viability is also critical. After all, many new stadia are paid for with public money, at least in part. Expensive white elephants are rarely part of the business plan.

That’s why multi-use facilities are becoming the default option for many new-build projects around the world. Owners want buildings that generate revenue all year round, rather than padlocked gates and empty seats for months or weeks on end.

Innovative, computer software-driven construction methods are making this possible. One such method is kinetic construction, which enables parts of a venue to move or change. Retractable roofs can make a stadium usable throughout the year, despite bad weather. Retractable playing surfaces increase the number of activities that can take place in a single venue. And dynamic façades can modify views in or out to heighten the mood of an event or increase participation.

AECOM Hunt is a pioneer in the use of kinetic construction for stadia and sports arenas, delivering a range of complex and technically demanding projects across the United States (U.S.).

As well as building eight of the 11 retractable roof stadia in operation in the U.S., AECOM Hunt built the first fully retractable natural grass playing surface in the U.S., at the University of Phoenix Stadium, and is currently building the first 360-degree video board, for the Atlanta Falcons.

Up on the roof

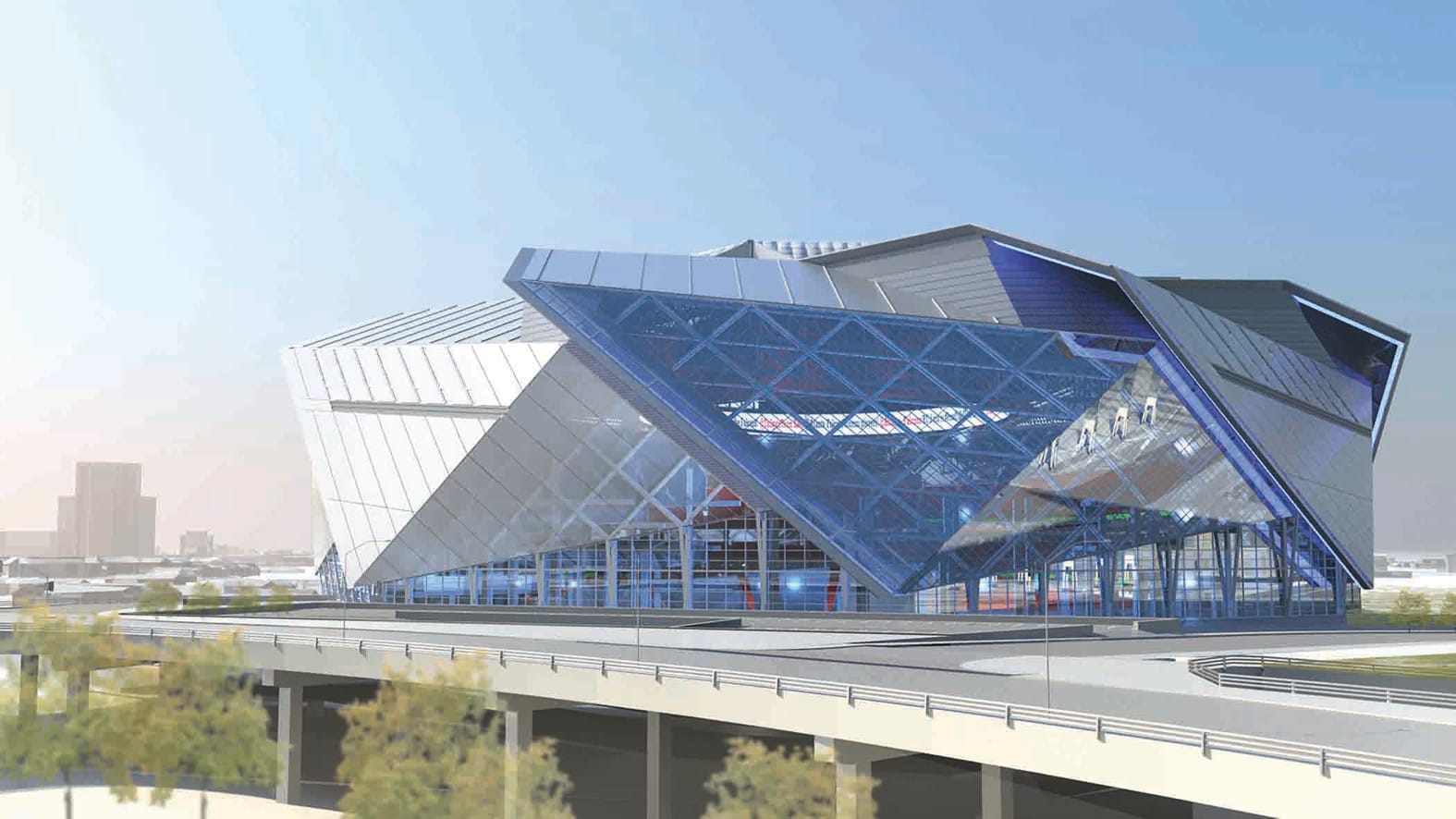

Atlanta Falcons Football Stadium,

Atlanta, Georgia, United States

Due for completion in March 2017, this new 72,000 seat-stadium will host NFL and MLS games as well as concerts, family shows and extreme sports, general public assembly events, stage shows and other special events. An extra 8,000 seats can be added to the stadium for major events like the Super Bowl or FIFA World CupTM.

Innovation

A retractable roof that opens and closes quickly provides tremendous flexibility in hosting a wide variety of events in the stadium.

How it works

Inspired by the circular ‘oculus’ opening in the Pantheon in ancient Rome, the stadium’s unique roof opening is made up of eight petal-like sections that can open in less than eight minutes. The structure is clad in a lightweight plastic polymer, called ethylene tetrafluoroethylene (ETFE) and allows for translucent light into the stadium when closed. ETFE is approximately one percent of the weight of glass, imposing significantly less dead-load on the supporting structure and reducing the structural framework required.

- The roof is made up of eight operable panels; triangular and cantilevered 200 feet.

- The panels will have linear movement thanks to 64 gravity and 24 up-lift transporter assemblies, creating an 110,000 square foot opening.

- In all, the roof weight 15,000 tons.

- The retractable structure is clad in 90,000 square feet of ETFE.

- The fixed roof is covered with 500,000 square feet of thermoplastic polyolefin roofing membrane.

- This entire roof structure is supported by 19 cast-in-place concrete large columns, 74 drilled piers and 410 auger cast piles for the mega caps.

Pitch perfect

University of Phoenix Stadium,

Glendale, Arizona, United States

Home to the NFL’s Arizona Cardinals, this is a 1.7 million square foot, 63,500-seat, multipurpose facility. The seating is expandable to 72,800 seats for special events. It also has 88 luxury suites and six levels including a service floor, retractable roof and roll-out ‘natural turf’ playing field.

Innovation

A unique moveable pitch and retractable roof means a greater variety of sports events can take place here, whatever the weather.

How it works

The stadium’s retractable playing field is the only one of its kind in the USA. It allows natural grass to grow outdoors and means the turf can be kept in great condition between games.

The turf sits in a 40-inch deep tray, which is mounted on railroad-like tracks. This means it can be brought indoors as required. The stadium’s interior concrete event floor can also be used for multipurpose events while the grass surface is outside.

- The field weighs approximately 12.75 million pounds and travels 740 feet into the stadium at about 15-feet-per-minute. That’s a total travel time of about 50 minutes one way.

- It rests on 13 railway-like tracks and is powered by 76 one-horsepower drive wheels. It travels on 340 16-inch-diameter idler wheels and 42 double-flanged guide wheels.

- The stadium’s roof is fully retractable and it is the first of its kind to operate at an incline.

- Its two moving sections sit atop 87-foot-tall, 700-foot-long Brunel trusses. These carry the primary load of the roof to four super columns at each end of the stadium.

- The roof panels are clad in a polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) translucent fabric.

- Each panel rests on eight roof carrier assemblies, two of which are cable drum carrier assemblies that move the panels 180 feet in approximately 12 minutes.

- The opening in the roof is approximately 100,000 square feet.

Turning the tables

Barclays Center, Brooklyn, New York City, United States